When work sends you to southwest England, and the dates shake out such that you get a free weekend after your conference, and you’re a polar fan, there’s only one thing to do….daytrip to Cheltenham! It was a four-hour round-trip journey by train from where I was staying in Exeter1, but it was absolutely worth it to see the hometown of Edward Adrian Wilson.

Wilson was born and raised in Cheltenham, and after earning his medical degree he went to Antarctica twice with Scott. As a mentor and friend he was beloved on both expeditions, as an artist he introduced many back home to the frozen lands of the south through his exquisite paintings with their attentive use of colour, and as a scientist he was the first to learn about the life cycle of the Emperor penguin. In addition to his character, I personally find his interdisciplinarity—doctor, naturalist, and artist!—hugely inspirational. The first time I went to Cheltenham last spring, I had read enough about him to know that it was his childhood spent exploring the landscape around Cheltenham that sparked his curiosity about the natural world—and I yearned to see his old stomping grounds myself. In this travelogue, I’ll take you through my (and Wilson’s) footsteps, with an addendum about my second trip to Cheltenham last month, to see an ongoing exhibition about his life and works.

Before getting on the train from Exeter, I did some research online. I owe a lot to the ‘Cheltenham in Antarctica’ walking tour and the Low-Latitude Antarctic Gazeteer.

The funny thing about visiting a place for a highly specific reason is it can blind you to the actual main attractors for tourists. I was suprised to see a sign about horse racing at the train station! Funnily enough, I had no idea Cheltenham had anything to do with horse racing2.

Famous for its mineral springs, Cheltenham became a spa town starting in the 1700s, hence the “Spa” in the name at the train station. On the edge of the Cotswolds and surrounded by rolling hills blanketed in verdant forest, the place has a rejuvenating effect even without stepping into a mineral spring.

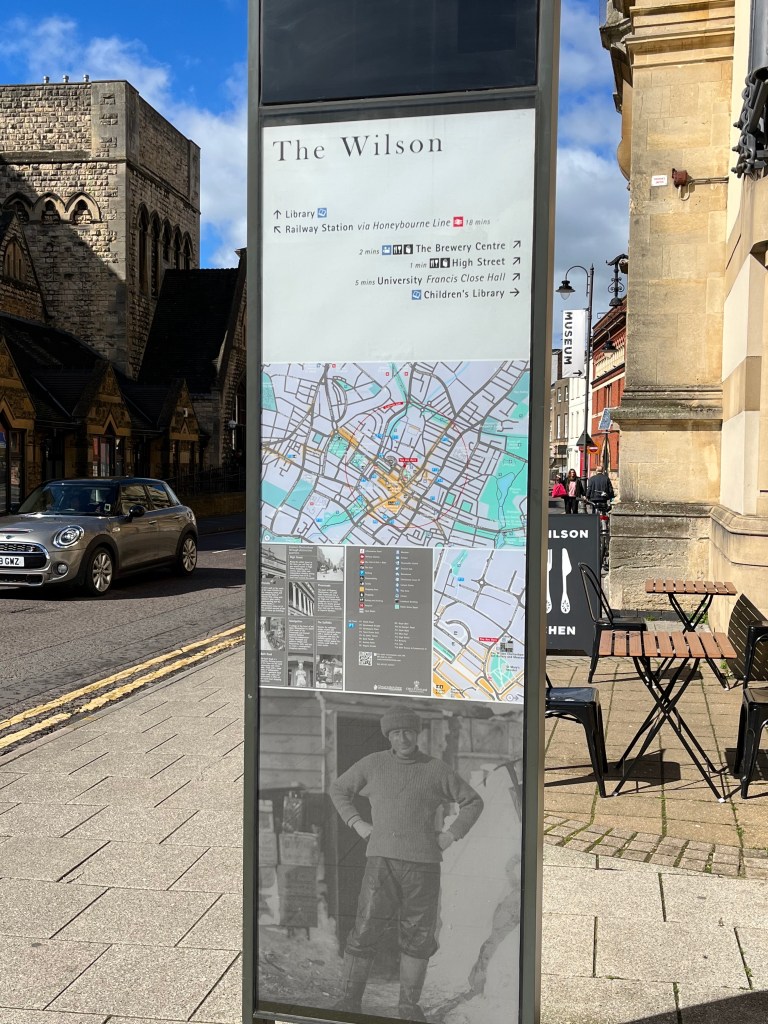

I had a big day of walking ahead of me. From the train station, it was a little over a mile into the centre of town to my first stop: The Wilson Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum. The Wilson family are prominent in Cheltenham’s history, and this museum was founded by Edward Thomas Wilson, father of Edward Adrian Wilson. Interestingly, it used to just be called the Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum, and was renamed for Edward Adrian in 2013.

Inside, I asked the desk attendant where I could find items relating to Edward Adrian Wilson. The museum is not focused on him, but has exhibits on a variety of subjects and art forms. The attendant directed me to the Open Archive.

I spent an hour in there, amongst old Wilson family photos, diary excerpts, scrapbook pages where Wilson collected bird feathers and flowers when he was a boy, paintings, and more! Particularly entertaining was a family Christmas wishlist from 1885 (Wilson was 13), where his list is miles shorter than those of all his siblings and he simply asks for “books on birds” and “drawing materials”. By a stroke of luck, I had the archive to myself the whole time I was in there. I pored over everything twice, and when I came to Wilson’s pocketwatch, recovered from his final resting place on the Ross Ice Shelf in 1912, I became as frozen as its unticking hands. It is stopped at 4:07.

Suitably sobered, I took a rest and lunched in the café, sitting under the wall of Wilson memorabilia. I had a long day still before me.

Next, I set out down the Promenade, a wide, tree-lined street full of shops and government buildings. It felt great to be out in the fresh air. Here I found the statue of Wilson in his polar gear, arms akimbo and weight shifted to one leg as he was wont to stand in photographs, and with his sketchbook on his belt. This statue was sculpted by Kathleen Scott (widow of Robert Falcon)3, using Terra Nova expedition members Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Thomas Griffith Taylor as models. It was unveiled in July 1914, just weeks before the start of the First World War, and it has stood over the Promenade ever since. There’s an info plaque in front of the statue, with a picture of the unveiling. In it, I could spot Clements Markham4, then an octagenarian, sat below the statue, roughly where I was standing. There was some guano on the plaque, but somehow I thought a bird-lover such as Wilson might not mind this. I walked round the base of the statue, and found Kathleen Scott’s name carved in the side. A kind passerby, very understanding of the awkwardness of solo travel, took the photo of me with the statue I’ve used at the top of the article.

On the way to my next site, I passed a wide spacious green, and reflected on how easy it was to see why Wilson loved this city.

My next stop was an empty lot.

This patch of grass was the former site of Westal, the home the growing Wilson family moved into when our Wilson was young. The second of the information plaques I came across is visible above.

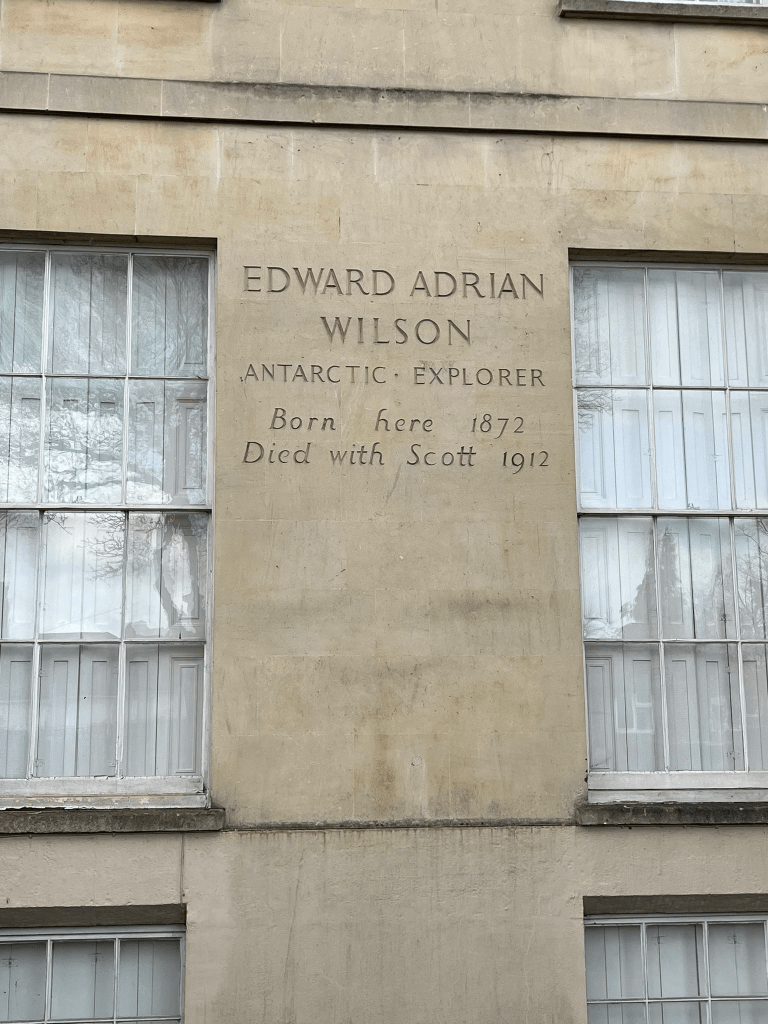

Just around the corner was 91 Montpelier Spa Road, the house Wilson was born in in 1872. As I read in his father’s memoirs in the Open Archive, “On July 23 a little red-haired boy was born who was afterwards to be our well loved ‘Ted’ of Antarctic fame”. Today this is a private residence, but there is a small commemoration carved on the wall that can be viewed from the pavement.

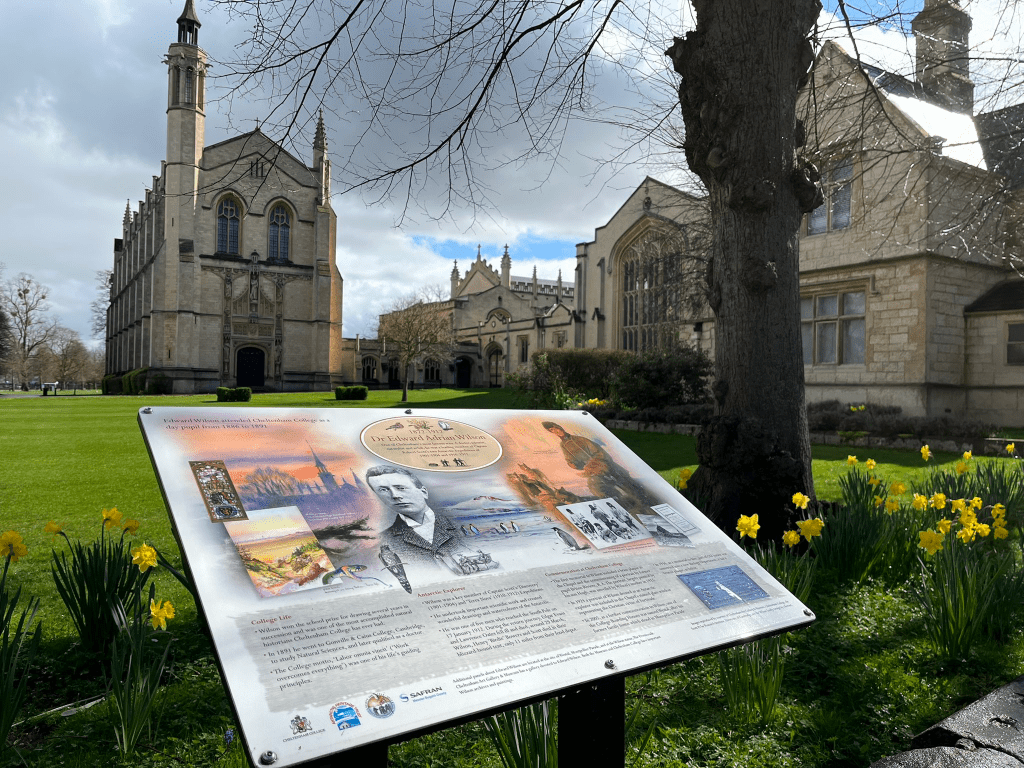

Most of the sites on my list thus far had been in close proximity, but now it was time to begin my long trek out of town. On the way, though, I stopped at Cheltenham College, where Wilson was a day student. Between Montpelier Spa Road and the College, I was drenched by a sudden burst of spring rain, but the sky was clearing up beautifully as I reached the third information plaque.

Cheltenham College is an operating school, and this was a Saturday, so I couldn’t go into any of the buildings. I did walk up to the chapel (the building on the left in the image above), and try and picture a young Wilson coming down to attend classes from birding up on Leckhampton Hill. During my second visit, I still couldn’t enter any buildings, but my friend and I did manage to spot Wilson’s memorial stained glass window from the outside.

The city diminished behind me as I first passed charity shops5 and cafés, then houses, then a church6 and a country fair, and finally farm fields. I found myself at the entrance to Crippetts Lane.

The Crippetts was a farm managed by the Wilsons from 1885 on, and it was there where young Wilson fell in love with nature. He would collect flowers and eggs, climb trees, sketch, and spend nights in the woods wrapped stock-still in a blanket, listening until he could identify not only the species of a bird making a noise, but also what it was doing at the moment. According to his friend John Fraser, quoted in Seaver’s biography of Wilson, “To see Wilson at his best, one had to go and stay with him at the Crippetts. There he was really at home and in his natural place. He knew every stick and stone, every hedge and tree in the neighbourhood.”7

It was quite the climb. The Crippetts is only three miles outside town, but it is all uphill, and steepest at the end. I worked my way up the winding road, heart rate climbing as I drank in the countryside around me. Daffodils sprung up from the ground as the leaves were just budding in the trees, and I was grateful my work trip had been scheduled for this time of year, for I couldn’t have been more fortunate on that front. The deep blue sky was not yet blocked by leaves over the tree-lined road, and puffy white clouds scudded lowly over the hills. I hope the reader will forgive me for the quantity of images to follow of my walk up to The Crippetts. Please picture a young red-haired man ambling about these environs, spotting birds’ nests a hundred others would miss.

After I’d worked my legs and lungs something fierce and was nearly at the top, I looked back and was rewarded with the view of Cheltenham spread out below me. Wilson often painted this exact view: see the little slideshow below, of a zoomed-in photo I took and a painting of Wilson’s from 1895 (from Cheltenham in Antarctica).

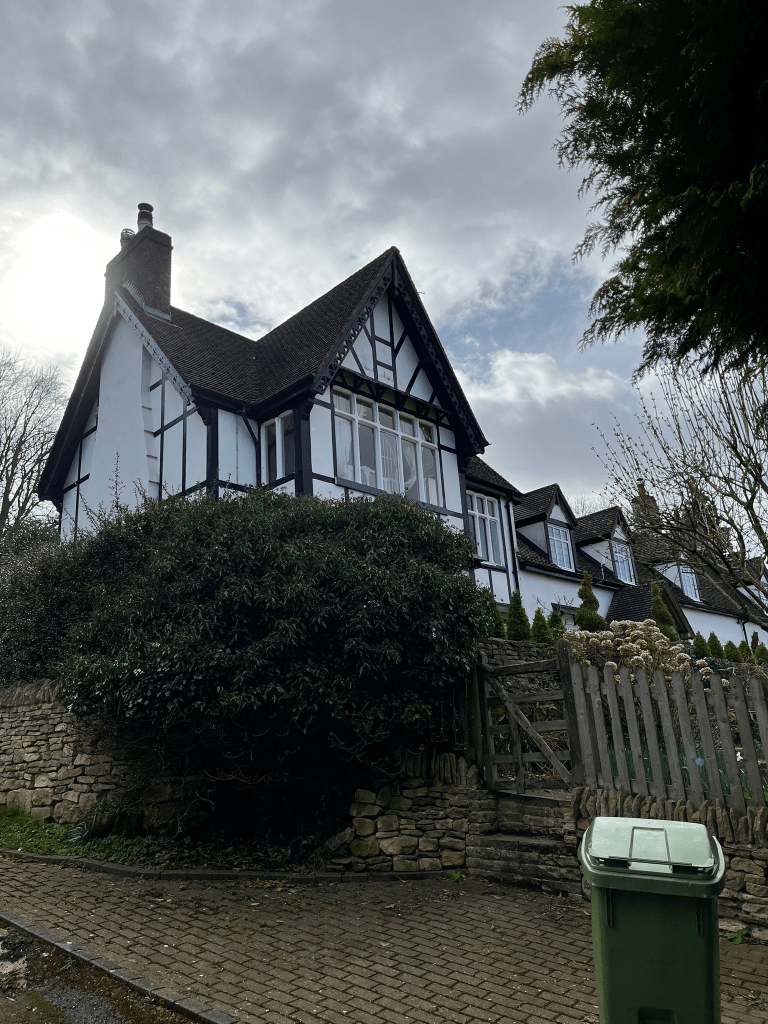

Finally, I made it to the black-and-white house itself. So strange at first to recognise a place from sketches and paintings! It’s a private home, so I did not approach any closer than the road, but I was able to see the blue plaque marking its historical import.

As the plaque says, “little piece of heaven” is right. I’m convinced Wilson is the sort who would have come to love nature wherever he was, but he certainly was blessed to get his first training as a naturalist in a site of such great beauty.

Unfortunately, the second painting I’d been hoping to match presented a much greater challenge. I could not get this angle from the public footpath in the field below the house, and the trees have grown differently in the intervening century.

Thinking of Wilson’s feathers and pressed flowers in the scrapbook back at the museum, I picked a daisy and a forsythia bloom and pressed them in my copy of his Discovery diary. If you’ve held a copy, you’ll know how well suited to flower-pressing the volume is. You’ll also know what a fool I am for having lugged a copy around during a day that included what amounted to 20.5 km (12.7 miles) of walking once all was said and done and I was back at my hotel in Exeter.

I believe that the places that are dear to us become a part of us, and it was a privilege to wander Cheltenham and see this place that was a part of Bill Wilson. Throughout his life and writings, the Crippetts were always on his mind. He compared distances in Antarctica to the walk from Westal to the Crippetts; when sledging blindfolded due to snowblindness he imagined he was swishing through bluebells in the warm Crippetts woods8. Seeing his childhood haunts myself gave me a different sort of information than I could ever have gained from a book or a museum: a new understanding. It was the perfect coda to the day. I trekked back to the train station and, happy and exhausted and having racked up a decent sledging mileage, I bade farewell to Cheltenham for the time being.

I would be back, of course, in October, when a friend and I visited the new Frozen Continent exhibit at The Wilson. As if to highlight the six months that had passed, the weather could not have been more opposite from my previous visit: it was staunchly grey, and spattering rain such that I was constantly wiping my glasses. The exhibition itself, however, was wonderfully done, and I was grateful especially to see reproductions of many Wilson paintings I had never seen before, particularly of non-Antarctic scenes9.

Unexpectedly, the exhibit also offered a chance to try on polar gear in the form of modern expeditioner Geoff Somers having lent his replica Terra Nova expedition gear for this purpose. I’d recently been watching Ben Fogle and Dwayne Fields’ Endurance: Race to the Pole10 documentary, and after watching them try on the gear I didn’t need to be asked twice!

Frozen Continent runs through 18 February 2024, and if you have the chance to get to Cheltenham before then, I highly highly recommend checking it out.

And there ends my first travelogue post! I hope you’ve enjoyed it. If Cheltenham is far for you, I hope it communicated a fraction of the experience. If Cheltenham is near, I hope it might help you plan. I already know I can’t wait to go back!

- Exeter Cathedral, by the way, is home to Scott’s sledging flag form the Discovery expedition (his Terra Nova one is at the National Maritime Museum)! Turn right just as you walk in and look on the far wall. ↩︎

- Being there for the University myself, I had a similar reaction to finding out St Andrews had anything to do with golf. ↩︎

- Kathleen Scott was a very talented sculptor who trained in France under Rodin. In addition to this statue of Wilson, she sculpted several memorial statues of her husband in the years following the tragic end of the expedition. I’ve seen the one in Waterloo Place in London, as well as the bust above the entrance to the Scott Polar Research Institute. They are made all the more poignant for knowing the personal connection of the artist. I cannot begin to imagine what this must have been like for her emotionally. ↩︎

- Clements Markham’s tenure as the President of the Royal Geographical Society was what kicked off the “Heroic Age” of Antarctic exploration for Britain. He was instrumental in planning the Discovery expedition—a forceful and controversial figure, but undeniably the only reason the Discovery actually set sail. ↩︎

- I found a very pretty hardcover copy of Mensun Bound’s The Ship Beneath the Ice for a tenner at one of the charity shops. Score! ↩︎

- This was the Church of St Peter, which, according to the LLAG, has a memorial cross for the Wilsons. This I passed because time was pressing and I wanted to make it to the Crippetts. ↩︎

- Page 20 of the 1933 edition. ↩︎

- From his Discovery diary. ↩︎

- I was surprised to see so many of Michael Barne’s cartoons from the Discovery South Polar Times, though! I wonder if any visitors leave thinking they were by Wilson! ↩︎

- Confusingly, the Endurance expedition is NOT one of the three expeditions covered in this documentary. I guess they just liked the title. ↩︎

Leave a comment