Note: this post involved a lot of independent research, and there are a lot of gaps in the story, especially regarding Quartley’s later life. If you spot anything inaccurate, or know of any information I’ve missed, feel free to reach out to me at glossopteris.polar@gmail.com. Thank you!

When thinking of the art of the 1901-1904 British National Antarctic (“Discovery”) Expedition, people’s minds rightly first go to the beautiful watercolours of Edward Adrian Wilson. Wilson was the official expedition artist, and a master of capturing nature truthfully, accurately, and elegantly. His body of work has earned him a place in history as one of the best artists—if not the best artist—to ever record Antarctica.

But there was another artist on the Discovery whose works I believe deserve attention. He was a Leading Stoker, but his class background was a bit more complicated than that position might suggest. He was one of the strongest sledgers on board, and many an officer complimented his physique in their expedition diaries or published accounts. He was the only man on board who did not grow up in the British Empire. He regularly contributed poetry and art to the South Polar Times. But he is hardly ever mentioned in the expedition accounts—unless you’re a polar history diehard, you’ve probably never heard of him.

Today, I want to tell you about Arthur Lester Quartley.

I think it was my second or third visit to the Discovery Point museum when Quartley really caught my eye. The exhibit includes a section about the crew and what they got up to during the polar winter. Quartley is one of four of the men highlighted in a little display near the harmonium, which reads:

Arthur Quartley was an American from Baltimore who joined Discovery as a stoker from the Royal Navy. At the time of the expedition he was twenty eight years old and had served on Captain Scott’s previous ship, the Majestic. He was a sledge traveller who took part in reconnaissance journeys to the South West and to the West. His total sledge travelling time of one hundred and sixty nine days was more than most members of the expedition.

Discovery Point Museum

Admittedly, he first jumped out at me because he was American. How did he end up on this British expedition?, I wondered. Then I noticed his name listed as artist under some illustrations on another display, and I became more intrigued by this artistic stoker from Baltimore. One illustration was done to accompany his poem “The Spook of Ski Slope”, featured in the South Polar Times. The sketchy style, with faceless figures and the ominous darkness, honestly brought to mind horror illustration. What on earth was that figure, skiing off into oblivion? I had to get my hands on the full poem.

I was able to read “The Spook of Ski Slope” courtesy of a friend who has a copy of the SPT, and I quickly drew a possible connection between the poem text and one of the biggest tragedies that took place during the expedition—the death of George Vince, who slipped off an unseen ice cliff during a blizzard on an early sledging journey. Might the poem and drawing be Quartley’s ways of processing the tragic events that led to Vince’s death? Quartley was a member of the sledging team in question, and with Vince almost to the last.

And that was it. I simply had to find out more about Arthur Quartley. As best I can tell, no one has written on him in volume before—he’s mentioned in some polar books, but, not being of the officer class, and neither going on any subsequent expeditions nor publishing his own account, there is very little material available about him. To add to the difficulty, he has the same name as his father, who was a maritime painter of some renown. Most Google results bring up information about the elder Arthur Quartley. This blog post aims to collate a brief biography from the primary, secondary, and genealogical record sources I’ve found on Quartley. A big thanks goes to Jessica Watkins, for her help and expertise with the genealogical research. This post wouldn’t be nearly as thorough without her. Let’s dive in:

Arthur Lester Quartley was born 23 July 1873, the third child and eldest son of Arthur Quartley (1839-1886) and Laura Louise Delamater (circa 1843-1881). His elder sisters were Adele (born 1866) and Grace Vilette (born 1870). The family would be completed with the birth of little brother MacDonough (called “Don”) in 1878. Our Quartley was born the same year his father opened his first art studio, and his childhood was coincident with his father’s rise to artistic fame. Before going into detail on Arthur Lester Quartley, it’s worth taking some time to go over Quartley Sr’s life and career.

Arthur Quartley Sr (I will be calling him this to differentiate the two, though I have no evidence he ever actually used the suffix) was born in Paris in 1839 to English parents. After spending most of his childhood in England, he and his family moved to the United States in 1852. Quartley Sr’s father, Frederick William Quartley, was a wood engraver, and provided illustrations to Appleton’s Picturesque America book. In addition to this familial artistic bent, it is possible Quartley Sr was trained in art as a boy at Westminster from 1848 to 1850—I have found some sources that say he was, and others that stress no artistic training. Upon arrival in the United States, the family settled in New York City, where Quartley Sr was apprenticed to a sign painter. He was successful in this trade and, in 1862, moved to Baltimore and opened up a firm, aptly named Emmart & Quartley, with a Mr Emmart. In 1864, Quartley Sr married Laura Louise Delamater, a New Yorker.

This brings us back up to 1873, the year Arthur Lester Quartley was born, and the year Quartley Sr decided to cut ties with Emmart & Quartley and become a studio artist full-time. He had been painting in his spare time for years, and now he successfully worked to establish himself as a maritime painter. Around this time, Quartley Sr started becoming frequently mentioned in the “Art Notes” sections of newspapers. In 1875 or 1876, he moved his growing family to New York City—a move foreshadowed by a December 1874 newspaper remark in which Quartley Sr complained that Baltimore was not the best environment in which to practice his art because most of his business was filling commissions from New York anyway. His time in Baltimore on the Chesapeake Bay had, however, been formative for his painting practice, and he never forgot the city.

So it was in New York City that young Arthur Lester Quartley grew up, in an artistic family, surrounded by culture and canvas and paints and visions of the sea. His brother Don came along in 1878, and his father became an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1879. The 1880 census captures both parents and all four children living together, along with one servant, a 29-year-old woman. His father’s career was thriving, and all signs point to Arthur having had quite a stable early childhood.

Then, in February 1881, Quartley’s mother Laura died suddenly and unexpectedly, in what must have been a huge blow to the entire family. Arthur was not quite eight years old. This would be the beginning of about five years of hard change for the family.

Now a widower, Quartley Sr debated travelling—and he did, going to Europe in 1882 and again in 1884 (amusingly only a few days after he became a naturalised American citizen). On the latter voyage, he brought all his children along: Adele, Grace, Arthur, and young Don. Thus, in May 1884, ten-year-old Arthur Lester Quartley embarked to sail across the ocean for the first time. Tragedy, however, struck again when Arthur’s little brother Don died of tubercular meningitis in July, shortly after arriving in England.

For the next year and a half, Quartley Sr and his three remaining children travelled through England, France, the Netherlands, and Italy. But Quartley Sr’s health began to fail as well: he suffered from jaundice while exhibiting his art in Venice. The family travelled home in 1886, but Quartley Sr never recovered, passing away from his liver condition in New York in May of that year. According to the Baltimore Sun of 8 April 1886, reporting on his illness, the death of Don had affected Quartley Sr’s health, as he “suffered a great loss in the death of a son…this is thought by his friends to have had a great effect upon his failing health, as his love for his children is one of his strong characteristics.”

Quartley Sr’s funeral was held in the library of the National Academy of Design, an organisation to which he had been admitted as a full academician just a week before his death. It was attended by his son and daughters, his brother Charles (also a Baltimore artist), and many grieving colleagues from the Academy, the Society of American Artists, the American Water Color Society, the Tile Club, and more. His obituary was published in several newspapers, and, in keeping with Victorian virtues around death, it was highlighted that he worked on his paintings until the end, and died at the peak of his career.

He may be said to have painted almost to the last, for he had an easel in the room he died in, got up and worked for an hour or two, and even painted in bed. The works produced under these conditions are among the best ever produced by the artist, who may truly be said to have died in his artistic prime.

“Mortuary Notice”, New York Herald, 20 May 1886

And so, young Arthur Quartley became an orphan at the age of 12. What happened to him next? Where did he live, before he joined the Royal Navy? Well…this is the part that was entirely a mystery to me when I began this research. I thought I was just going to have to offer a few suggestions and fast-forward to Antarctica, but as it turns out, newspaper archives are incredible things. A lot remains uncertain, but bit by bit, Jess and I have pieced things together. Here’s what we have.

It is likely Arthur remained living in New York. His eldest sister Adele was 20 years old when their father died, and it is quite possible the three siblings could have lived together, perhaps supported monetarily by their uncles. The aforementioned uncle Charles who was present at the funeral is a strong candidate. Moving away from the realm of speculation, it seems certain from newspaper records that the three siblings lived on Staten Island. Arthur’s sister Grace appears several times through the late 1880s in newspaper reports about tennis (she played doubles) on Staten Island. In 1888, Arthur gave away his sister Adele at her wedding—this is one of the strongest records I have found of Arthur during this time period. In 1890, his sister Grace got married as well, but reports indicate she was given away by her brother-in-law. Where was Arthur? I don’t know. Perhaps he was ill, or away. I cannot even be certain he was living on Staten Island in 1890, because the 1890 census records were lost in a Commerce Department fire in 1921. However, it seems he was there before and after: in 1888, I have a likely record of him playing American football for the Staten Island Cricket Club juniors, and from 1892-1895, I have found several newspaper mentions of an Arthur Quartley rowing for the Staten Island Athletic Club—Jess and I can’t find any other Arthur Quartleys alive at this time, so we are almost certain this is him.

In 1886 when Quartley Sr died, Arthur was 12 years old. In 1896, when he joined the Royal Navy, he was 22. What did he do during that decade, aside from sports? Certainly there must have been some amount of schooling, though I have no records for this—I suspect he didn’t go to university because he probably would’ve turned up in sports reporting if he had. What was he up to, as his sisters were getting married and starting families? Was there anything to presage his naval ambition? This was where Jess and I had our eureka moment: it seems that, like his father, Arthur couldn’t resist the call of the sea.

The United States did not officially have a National Naval Reserve until World War I. However, there had been appetite for such a force long before then, with a bill to create one defeated in Congress in the 1880s. As a result of this defeat, naval militias began forming at the state level. New York became home to the second of these state naval militias when the First Battalion, Naval Reserve Artillery mustered into service on 23 June 1891. I was clued into the idea that Arthur might have been a reservist when I found an 1893 New York Herald article mentioning a “Quartley” as among the best performers during target practice on the First Naval Battalion’s summer cruise. Lo and behold, a bit more searching turned up 17-year-old Arthur Quartley as one of these very first American naval reservists.

During his time with the reserves, he would have drilled weekly at Castle Garden, received a call for active duty to prevent violence towards disembarking cruise ship passengers on Fire Island during a cholera breakout, participated in summer training cruises, and taken part in ceremonial duties like an honor guard for President Harrison and parades for World’s Fair Celebrations. Joining the First Battalion, Naval Reserve Artillery put Arthur right in the middle of a fascinating piece of US naval history, and his time there seems to have cemented his choice of a naval career. Clearly, he took to the life, and wanted more of the sea. He was an active, fit young man, and weekly drilling and regattas were not enough: so, naturally, he joined the Navy.

Just one little catch, though. He didn’t join the United States Navy. No. On 21 May 1896, Arthur Quartley joined the Royal Navy.

Huh?

The last record I have of him in the US is a newspaper article about winning a crew race in July 1895. At some point between then and May 1896, Arthur made the decision to move to England and join the Royal Navy. What’s more, he joined as a stoker.

It’s one of those decisions I wish I could ask his ghost about, and one of the things I find endlessly fascinating about him. In New York, the Quartleys were members of society—their weddings and social and sporting activities were constantly in the newspapers. Arthur’s father was a famous artist; he had family, friends, and connections; though familial wealth is hard to determine he seems to have been upper middle class. In 1896, Arthur moved across the ocean to a country with a more entrenched class system, and joined its Navy in a working-class position and at an older age than usual (22). I can and do speculate in vain about this. A call to adventure, to the sea, I can understand, but why, after being in the New York naval reserve, did he not join the US Navy? Perhaps he wanted to join the British Navy out of his family ties to England? Perhaps those ties even made him eligible for citizenship? Perhaps the trip he took to England when he was a boy left him certain he wanted to return one day? Perhaps he just had a Quartley-life crisis and needed a change and to be far away….if you’ll forgive the horrendous pun.

We will probably never know.

But join the Royal Navy as a stoker, Arthur Quartley did. His service record mistakenly lists his birthplace as London, and describes him physically as 5’10.5″ tall, with red hair, grey eyes, and a ruddy complexion. His first ship was the Victory II. He would have been thrust into a completely new world: new country, new job to learn, and strict new Naval discipline to follow. Over the next few years, he learned the ropes. The 1901 UK census found Arthur in Plymouth, living as a boarder with a petty officer as head of house. (The nearly-contemporaneous 1900 US census found his sister Adele living with her husband, three daughters, and four servants in Manhattan.) Arthur was 27, single, and ready for the adventure that was just on the horizon.

For a brief period in 1897, Arthur had served on a massive warship called the Majestic. He returned to work on her longer-term from July 1898. It was on the Majestic that Arthur worked with a young torpedo lieutenant named Robert Falcon Scott—if the newspaper report of Arthur’s artillery prowess with the reserves is anything to go by, it is easy to see how the two might have ended up interacting. Scott had won the leadership of the upcoming British National Antarctic Expedition, and when the expedition’s overseeing committees granted him the power to select much of his own crew (who would be released by the Admiralty) he naturally gravitated towards his known and dependable shipmates from the Majestic. Scott asked for volunteers, and Arthur Quartley put his name forward. He was accepted, along with his boss from the engine room, Engineer Lieutenant Skelton. Skelton and Quartley joined other shipmates from Majestic who would go on to become very famous names in Antarctic history, like Edgar Evans. Upon selection for the expedition, Arthur was promoted to Leading Stoker.

Arthur would travel south on a custom-built sailing ship called the Discovery and spend the next several years living and working in Antarctica, a then-almost-wholly-unmapped region at the bottom of the globe. He would be unable to contact his family and friends for up to a year at a time—if all went well. On top of all that, it would be devilishly cold. If his leap of faith to join the Royal Navy provided him any preparation—albeit of a different order of magnitude entirely—for taking such a plunge, it’s safe to say he needed it.

Before detailing Arthur’s time on Discovery, it’s time to talk about where I’m pulling it from: what records I have found of Quartley’s time on the expedition. Mostly, it’s important to note that I have very little of Quartley’s own writing. Most of my information comes from outside perspectives, usually officers mentioning Arthur in their diaries. Skelton, as his boss in the engineering section, writes about him most frequently. The only written sources from Quartley himself I have found are his contributions to the South Polar Times, and a single long excerpt from his diary that Skelton quotes in March 1902, regarding the disastrous Cape Crozier sledging journey. Doubtless there is more information about Quartley in archives—I have yet to read all the archive-locked Discovery diaries—but what seems to be missing as far as I can tell is his aforementioned diary. At least, the Scott Polar Research Institute doesn’t have it. All that I can find of it is this quoted passage in Skelton’s diary. When other polar writers, like Baughman in Pilgrims of the Ice, quote Quartley’s diary, it is also just from this section Skelton reproduced. Is there more of Quartley’s diary out there? What happened to it? I would love to know—please reach out if you have any information! For the purposes of this post, understand that the sources I have are mostly biased to the officer perspective, except for the SPT writings.

Arthur was part of the stokers’ mess, a group that also included William Lashly, who would go on to join Scott’s Terra Nova expedition as well. According to Skelton’s diary, the stokers’ mess was “about the best set-up department of men in the ship” (28 Feb 1902), aside from one or two troublemakers. Skelton, who can tend towards both gossip and classist remarks at times in his diary, describes several instances of men drinking overly much on the voyage south, but Arthur seems never to have been among these. Despite the condescension in the privacy of his diary, Skelton seems to have been a fair boss, easy to know what to expect from, and he and Arthur mostly got on well. On one occasion Arthur designed a more efficient shovel for use by sledging parties; on another he built a bookshelf for Skelton’s cabin.

Early days after the ship established a Winter Quarters in Antarctica were full of hustle and bustle. It took a long time for the ship to become fully frozen in, and this made going to and from shore difficult. There was much to be done. In addition to helping build the main and scientific huts, Arthur’s mess had to prepare the engine for overwintering. As well, a record of the location of the Discovery‘s Winter Quarters had to be left for the relief ship to find them. As winter was closing in, this had to be done quickly. This sledging journey would contain what Scott later called “one of our darkest days in the Antarctic” (VOD).

On March 4, 1902, twelve officers and men set out with most of the dogs to leave a map at the pre-arranged location of Cape Crozier, known from Ross expedition days. Those men were Royds, Koettlitz, Barne, Skelton, Wild, Hare, Vince, Weller, Evans, Plumley, Heald, and Quartley.

It was brutal. The party’s total lack of experience quickly became apparent as progress was slow, sledges were inefficiently packed, and a disorganised combination of manhauling and dog-pulling was used. Arthur was sharing a tent with fellow ratings George Vince and Isaac Weller. He quickly learned that routine tasks like dressing, cooking, and setting up camp took far more time and care than under warmer conditions. Just melting socks into a position in which one was able to slip his foot in was difficult. According to Skelton’s diary, on 5 March 1902 “Quartley had a cold foot for a very long time, so that the other party had to camp & change his ski boots for Finnesko”. Royds, as quoted in Scott’s expedition account, corroborates this. Finnesko were made of insulating fur, and unlike leather boots, they were bendy, allowing circulation and warmth to be maintained. The tradeoff was that finnesko were far slipperier, having no grippy sole. Certainly everyone was learning how best to manage their footgear to avoid frostbite on this early journey. Perhaps this incident inspired Quartley’s generosity towards Vince later.

As it became clear progress was happening too slowly, and that they had brought an unnecessarily large party, the officers held a meeting. They decided that Royds, Koettlitz, and Skelton would go on as a smaller, quicker team, and Barne would lead the men back to the ship.

Doubtless, no one was too disappointed at the early abandoning of their mission. Sledging is unpleasant for the well-trained; it must have been hell for such an unprepared group. On March 11, Barne and the men were almost back at the ship when a blizzard started to blow. At first, Barne ordered everyone to camp—shelter in place. But when the primus heaters did not work, which meant no hot food, Barne made the decision to pack up and make for the ship. Arthur helped prepare his tentmates for the dash back, but now it was his tentmate Vince’s turn to have foot trouble:

Vince’s feet began to freeze, in my tent, & he took off his boots, thinking to restore circulation. I had a pair of fur shoes in my breast & gave them to him….We remained about one hour on this spot. Lieut Barne then thought that we had best try & make the ship. He therefore ordered the tents to be packed up & everything to be replaced on the sledges, which was done. I told Vince to put on his boots again as he would find it hard work to walk in the fur ones. I also told the men in my tent to wrap up in warm clothes as we would perhaps be some time in making the ship in the blizzard.

Arthur Quartley’s diary entry for 11 March 1902, as quoted in The Antarctic Journals of Reginald Skelton: Another Little Job for the Tinker, ed. Judy Skelton

The group’s next movements were a complicated jumble. Barne attempted to lead the men along a ridge to where he thought the ship was, but the blizzard had rendered visibility to near-zero and made hearing each other utterly impossible. Vince had not listened to Arthur’s advice—he was still wearing Arthur’s finnesko, and was having trouble keeping his footing on the ice in the wind. Another man, Hare, had also worn finnesko, and turned back to get his leather boots without the party realising. In the process of spreading out to look for him, Evans slipped and careened out of sight. Barne almost immediately slid away after him. A few seconds later, Arthur decided to follow suit.

When he slid to a halt, he found that he, Evans, and Barne were stuck on a snow ledge—horrifyingly, the sea was just over the edge. In the blizzard, the men had been trying to go in completely the wrong direction and were dangerously near a cliff. But stuck below, they could not climb back up the steep hill they’d come down to warn the others. They tried to make their way back diagonally along the ice foot. According to Skelton, the trio were out for 14 hours in the blizzard. They nearly froze to death before hearing the ship’s siren, which gave them hope. Here is Quartley’s account of their rescue:

We had not gone a half mile when I saw a black speck that seemed to be moving…I called the attention of the others to it, but they seemed to lack interest in anything, & it came to me that the cold was gradually getting the better of our senses, so I forced the pace…I saw about 15 men all together coming towards us,…& I heard Mr Armitage’s voice say ‘where is Mr Barne?’ Mr B did not answer & neither did Evans. Then I said ‘That is Mr Barne’ pointing to him, ‘That is Evans’ pointing to him, & ‘& I am Quartley’. Then Mr Armitage asked where Hare was…& I heard Wild’s voice, so knew he was safe. Then someone said Vince was gone…

Arthur Quartley’s diary entry for 11 March 1902, as quoted in The Antarctic Journals of Reginald Skelton: Another Little Job for the Tinker , ed. Judy Skelton

After Arthur had slid down after his companions, those remaining on the ridge had decided to press on. Soon after, that group found themselves falling down the steep slope as well. All of them were able to arrest their fall on a lip of snow just above the cold black sea—all except for George Vince, wearing Quartley’s borrowed finnesko, who plummeted off the slope and into the sea, where he surely froze. His body was never recovered. Vince was the only death in Antarctica during the Discovery expedition. Still today, he is commemorated by a cross at McMurdo. Arthur and the men of Discovery paid a terrible price for their experience.

Back on the ship, the expedition settled in for the long winter, determined to meet the spring sledging season better prepared. But winter brought not only darkness and toil, but also fun and games to keep up morale: in late March, the officers settled on the name The South Polar Times for their monthly shipboard newspaper. Anyone could contribute, and the editor, Ernest Shackleton, would decide what would be printed. The SPT ended up containing everything from scientific notes to parody play scripts to poetry and caricatures. It provides an excellent window into the social life onboard—albeit rife with in-jokes it can take some serious research to understand, especially because almost no real names were used (writers employed pen names). Partially for this reason of inaccesibility, only a handful of researchers seem to have written about it in detail. If you’re interested, it’s well-worth seeking out and can be very rewarding for understanding the characters of the men and the playful side of expedition life. It’s a big part of how I got interested in Arthur Quartley.

Arthur would eventually contribute plenty to the SPT, but he sat out the first issue, which came out in April 1902. He did not go without mention, though, as his crewmate Frank Wild (writing under the name Shellback) described him thusly in a piece entitled ‘Some of My Messmates’:

Obadiah Ginger, of the same house [read: mess], was, it has been stated, one of the most brilliant conversationalists ever turned out of the United States of America; when away sledging, a rush was always made to get into his tent, as, owing to the warm tint of his hair, the temperature was usually several degrees above the others.

Frank Wild, April 1902 South Polar Times

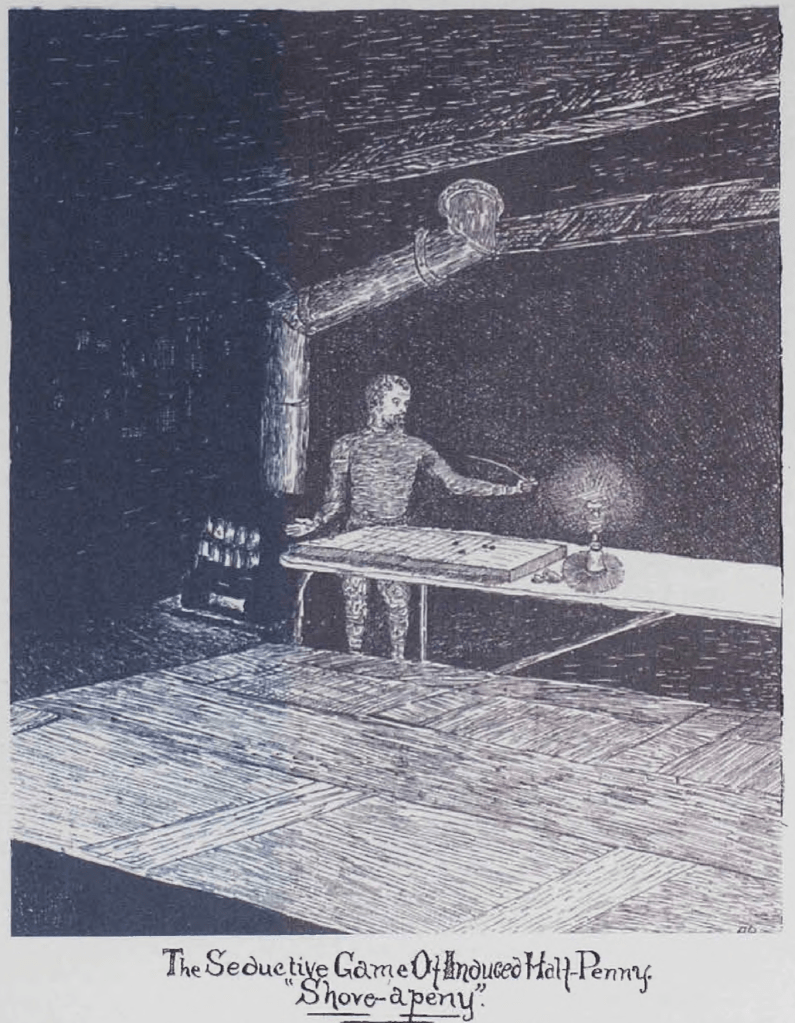

Wild’s article provides a great example of the humourous tone of much of the SPT. SPT articles often use joke names for others, which may or may not have been actual nicknames, but in this case, since the other pseudonyms in this article are clearly based on the individual’s name whereas “Obadiah Ginger” comes from nationality and appearance, I suspect “Obadiah Ginger” was an actual nickname people called Arthur. I know from Wilson’s diary that Arthur was called “Ginger”, and I could easily see Arthur’s crewmates joking that “Obadiah” sounded American and calling him that. Arthur seems to have been popular on the mess deck, and friendly with Frank Wild, who was on his first of what would eventually be five Antarctic expeditions. In the May SPT, Arthur made his first contribution, writing up the results of a Shove Ha’Penny tournament won by Wild. Arthur wrote “As reporter for the S.P.T., I requested Mr. Wild to allow me to make a sketch of him with his famous pipe; an immediate affirmative was given.”

This was Arthur’s first illustration for the South Polar Times. I’m no art critic, but I find his a unique and enigmatic style. Even aside from the different medium, his inked crosshatching and strong contrasts between light and dark feel very removed from his father’s work. Arthur’s style also stands out amongst his fellow SPT artists: not as precise as Wilson’s nor as cartoonish as Barne’s caricatures. When Arthur draws darkness, it feels almost as if there is something in the darkness—as if it has weight, a depth—I think this is why it reminds me of horror illustration. I love it.

At the beginning of every month, the doctors Koettlitz and Wilson took height, weight, and other measurements of every man on board. This was to create a record to determine if the polar night was affecting the crew’s health—but it also turned into a game, the men filling with jibes, merriment, and competition. Arthur was tall, strong, and very physically fit, and everyone considered his results impressive at the monthly measurements. His physique was a consistent feature of his reputation on board; it is mentioned in nearly every account of him I can find. I would be remiss not to include them. Skelton describes Quartley as “certainly the finest specimen” (28 February 1902) among his men and says he “beats all the records at almost everything” (4 June 1902) when the doctors take the monthly measurements. Armitage, the second-in-command, later wrote “Quartly [sic] was, I should think, the most powerful man on board the ship. Being about 6 feet in height, and beautifully proportioned, he certainly presented the handsomest figure among the ship’s company.”

In addition to more praise of his physique, Wilson provides a character sketch of Arthur in his diary:

It was my night on duty, a fine clear cold night and Quartley was on duty on the mess deck. Quartley is an American, and a very striking personality. He is quite the finest figure of a man I have ever set eyes on, standing just six feet and a perfect giant in strength and sinew. He is educated much above his position in the Navy, in which he is a Leading Stoker, and his father he says was an artist by profession. He is a splendid looking man, tall and immensely powerful, but one of the quietest and most retiring men on the mess deck. He is known as “Ginger”, having wavy red hair, and a red beard since we have been down here. I have had a good deal to do with him at odd times through the S.P.T., for which he has generally written a piece of poetry and drawn or painted a picture. I gave him the cover to do for the last number. I let him take all my sketches and bird drawings on the mess deck to amuse him during his night watch. He reads incessantly and I have never seen him play cards or any other game in his mess.

Edward Adrian Wilson, Diary of the ‘Discovery’ Expedition (ed. Ann Savours), 25 August 1903

It is very clear Arthur more than passes muster in the doctor’s eyes. Wilson also gives us a few more insights into Arthur’s character: despite reporting on and drawing the games for the SPT, Arthur seems to partake less in draughts and shove ha’penny than the others, preferring to read and enjoying poring over Wilson’s drawings. Wilson also confirms Arthur was “educated much above his position in the Navy”.

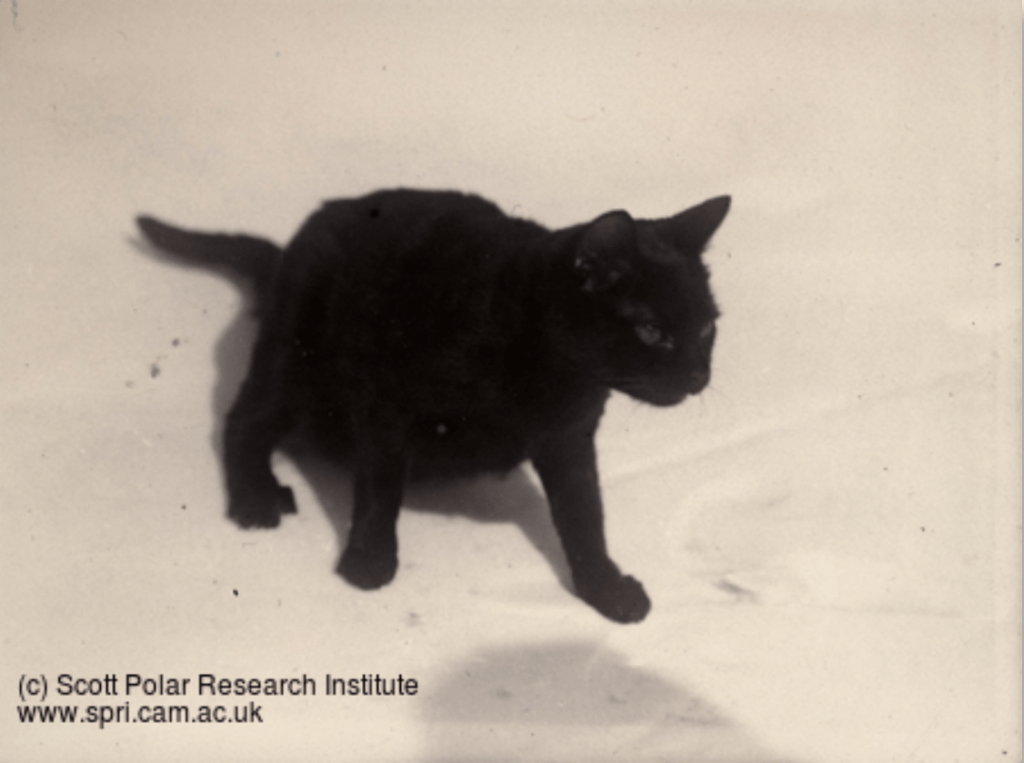

During the winter, the men only had to work half-days and had the entire afternoon and evening off. Even taking daily exercise in the form of a walk or ski, Arthur would have had plenty of time for reading and other pursuits, like writing his poetry. By this time he had also become enamoured with Blackwall, one of the ships’ cats, whom everyone considered to basically be his.

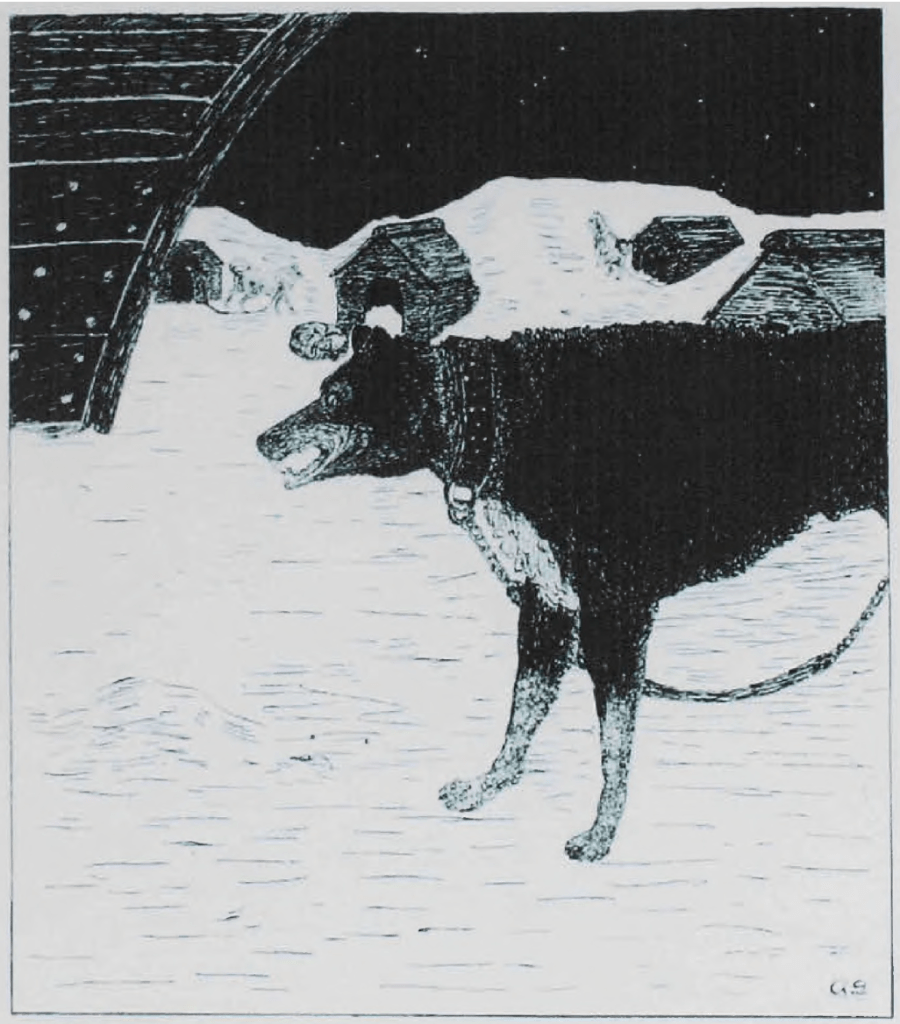

In July 1902, Quartley’s first poem appeared in the SPT. He wrote under the pen name “Sea Leopard”. His poem was called “The King Dog of the Sledge Pack”, and was accompanied by a drawing of the lead sledge dog.

The lead dog of the sledge pack’s name was a racial slur, and I will not include it for that reason. But equally I think it is important not to ignore the fact that these White, Edwardian men did bring their prejudices with them even to a new continent. I say this to counter a prevalent narrative that exists that Antarctic exploration was somehow “purer” or “less problematic” than other forms of exploration in which explorers interacted with and directly harmed native peoples. Nowhere is it more obvious that the explorers brought their prejudices with them than in the fact that Lieutenant Royds organised a minstrel show in the August of the first winter. A minstrel show was a racist theatre event in which performers donned blackface and acted out negative and harmful stereotypes of Black people. These shows continued until horrifyingly recently: as late as the 1970s, The Black and White Minstrel Show was on British television. Arthur Quartley was not among the blackface actors in the Discovery‘s minstrel show, but we know from an interview given by Shackleton to The Macon Telegraph in 1903 that Quartley provided plenty of song material and racist “dialect recitations” to the performers. The presence of this show on the expedition I have often found to be glossed over, and I do not wish to contribute to this. For more on the history of blackface in polar exploration, I recommend Mossakowski’s “The sailors love dearly to make up”, available here.

Later in August, “The Spook of Ski Slope” appeared. If you recall, this is the poem that got me really fascinated by Arthur. “The Spook of Ski Slope” weaves a folk-story-esque narrative, in which our protagonist is skiing near the Discovery and comes across a devil-like figure, flying above the snow. The figure is skiing towards danger, so the protagonist follows him in an attempt to provide aid. Instead, the figure challenges him to a race. They race down Ski Slope, with the protagonist winning the figure’s golden ski. The devil-like figure then offers to race again, asking what the stakes are to be. Boastful, the protagonist accidentally stakes his very soul, certain no one can beat him with only a pole (as he now has the figure’s ski). As the second race begins, he realises to his horror that the golden ski strapped to his feet go wherever the figure commands them to. Unable to control his skiing, the protagonist flies off the edge of the land to “perish in the deep”. Then, the tone shifts. The protagonist wakes up on the ship, and is told off for disturbing others with his bad dream. He explains he fell while skiing that day, and will never go to Ski Slope again.

The deal-with-the-devil nature of the story—and the detail of the golden ski—immediately brings to my mind “The Devil Went Down To Georgia”, which of course would not come out for decades after the Discovery expedition and has a much more upbeat conclusion (for an even deeper cut, the poem reminds Jess of the Black Racer). The poem’s downer ending, however, is more in line with most deal-with-the-devil stories: the devil wins. The extra twist of it all being a dream is interesting. My personal interpretation—and I do want to stress this is my informed speculation, not fact—is that writing “The Spook of Ski Slope” might have been a way for Arthur to process the death of George Vince. The presence of the devil-like figure, who could certainly be considered an avatar of death, along with shooting off an icy slope “to perish in the deep” and the protagonist’s struggle with nightmares all indicate Arthur was confronting the challenges of mortality involved in polar exploration. Art therapy, of course, did not formally exist at the time—but that doesn’t mean people haven’t been using creative expression to understand their feelings, even subconsciously, since time immemorial. I’ve included the full poem at the end of this post, if you want to give it a read yourself!

Winter thawed into Antarctic spring, and it was time for the new sledging season. Arthur went on an early journey in September 1902, the goal of which was to find a route up the Western Mountains. The party consisted of Royds and Koettlitz for the officers and Quartley, Wild, Evans, and Lashly for the men—a strong, dependable group those on the Mess Deck were already referring to as the “Guarantee Party”. Unfortunately, the journey was cut short when Lashly’s sleeping bag blew away. Lashly had been in the officers’ tent, where each person used a single sleeping bag, and was forced to squeeze into the three-man sleeping bag already shared by Quartley, Wild, and Evans on the uncomfortable trip home. They all had to turn over together, and no one can have had much sleep. Clearly, everyone was still learning the lessons of sledging—including what an eagle eye was needed to prevent things blowing away.

After some recuperation at the ship, Arthur was part of Royds’ renewed effort to, once and for all, place the Winter Quarters map at Cape Crozier (the officers who had gone on the last spring after the men returned to the ship had been forced to turn back by weather). The composition of this group was the Guarantee Party, Royds, and Skelton. This mission, finally, was a resounding success: not only was the message safely delivered, but an amazing discovery was made at Cape Crozier.

Before the Discovery expedition, the life cycle of the Emperor penguin was a complete mystery. It was assumed that no creature could live in the Antarctic winter, and that the penguins must migrate to a warmer climate for part of the year. But in October at Cape Crozier, Skelton, Evans, and Quartley found Emperors and followed them to a rookery. Out on the ice around them they found hundreds of squacking birds, live chicks, dead chicks, and shards of eggs. It was obvious that not only did the Emperors stay in Antarctica over the winter, but they bred in the winter. Truly this was a momentous discovery for natural science. The men collected specimens to take back for the ornithologist, Dr Wilson, who would no doubt be over the moon about this find—once he returned from his own long sledging journey.

Back at the ship, the King’s birthday was celebrated with a Sports’ Day (the price of admission was jokingly set as an Emperor’s egg, no doubt a nod to the recent exciting discovery). Unlike the protagonist of his poem, Arthur was evidently not entirely scared of Ski Slope, because he won the toboggan contest, along with his partner, donkeyman Thomas Hubert (a “donkeyman” looks after not animals but the “donkey engine”, a sort of steam winch). Tobogganing was a common recreation among the Discovery crew, who built their own crafts out of skis and packing cases. Judging from Skelton’s and Armitage’s accounts, it seems Arthur was the force behind this team, having built a Canadian bob-sleigh, and Hubert was largely along for the ride. Winning the toboggan race turned out to be less about speed and more about not capsizing, and the two had built the only steerable sleigh and thus avoided rocks and other obstacles. Arthur did well in the other events too, including tug-of-war, and was awarded his prizes by a princess—marine Gilbert Scott in drag.

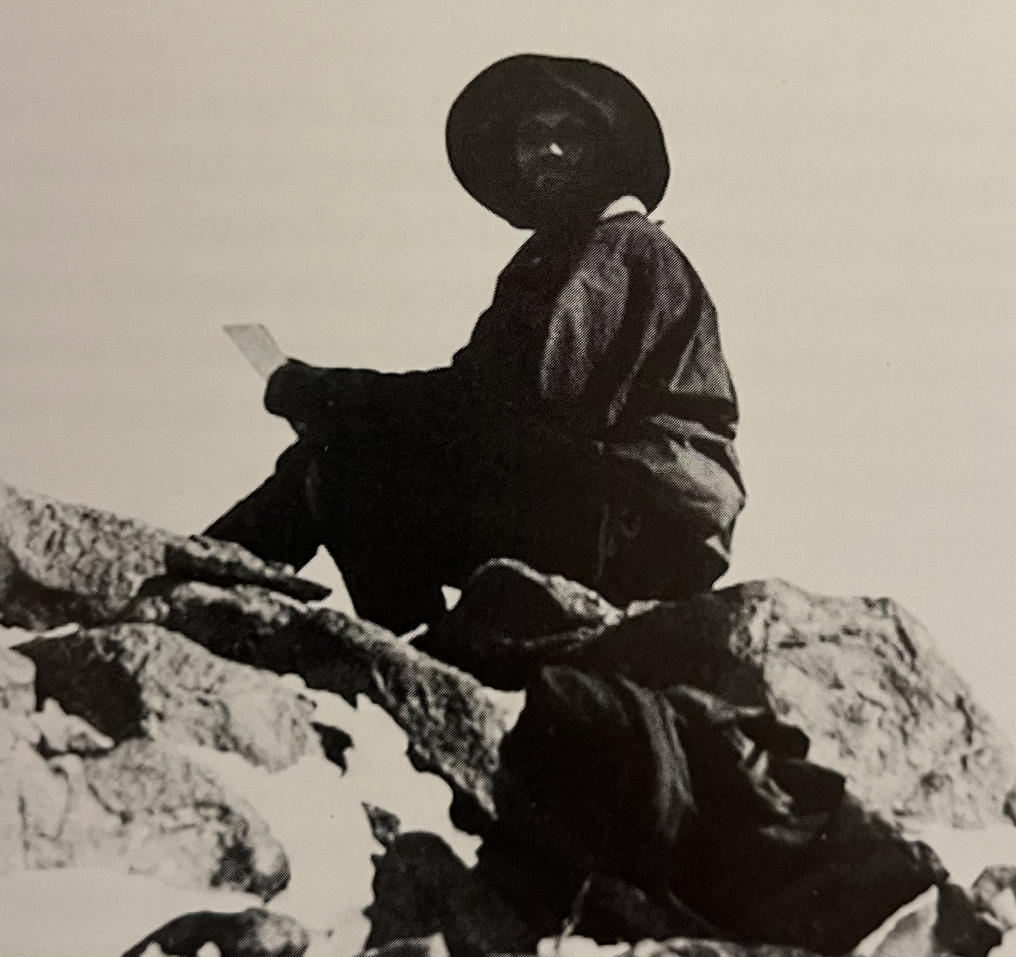

Arthur was part of the main Western sledging party in summer 1902-1903. This group was led by Armitage and was tasked with summiting the Western Mountains. This they eventually did, though not without much stop-and-go and great effort as they invented ways to climb glaciers and icefalls with heavy sledges. At the summit of Victoria Land they discovered the Polar Plateau, that seemingly endless high desert of white. As an artist of some recognised talent, Arthur was tasked on this trip with a lot of panoramic sketching to map new terrain. It was bitterly cold work, but important in case the cameras failed.

On December 18, while still ascending, Arthur spotted something strange on the ground—a dead seal. It was very dead, decayed and dessicated—and it was 15 miles from the face of the glacier and 2,500 feet up. Arthur and the others found it a complete mystery how a seal could have ended up so far from the sea. (Researchers today think such mummified seals indicate changing climate conditions, and perhaps died in warmer times).

By early January, Armitage’s main team (which included Arthur) had reached the plateau. They could see nothing but white to the west, no sign of a coast. As best they could tell, the plateau went on infinitely. It must have been a desolate sight—only made bearable, as Scott wrote after seeing it a year later, by the allure of the unknown.

On the return journey, Armitage fell down a crevasse in a scary and memorable incident (ironically he had just been telling others to watch out for crevasses). Arthur was there during his rescue, keeping the sledge steady while the others lowered a bowline. He later illustrated the event in the SPT. Around this time there seems to have been some friction between Arthur and some of the men, on one side, and the party’s leadership, on the other. Skelton complains in his diary of Arthur making nasty comments about the leadership:

At one of the halts, Quartley made some very objectionable remark in the hearing of Armitage & self, about ‘going all over the ——— shop for nothing’. I suppose he was tired & hungry, the biggest & strongest man in the party, & as I have always supposed by birth & education much superior, but apparently he is a ‘weather cock’ – shouts Hurrah one day, when Armitage is hauled out a crevasse, & uses dirty insulting language another.

9 January 1903 entry in The Antarctic Journals of Reginald Skelton: Another Little Job for the Tinker, ed. Judy Skelton

Given Skelton himself complained about Armitage’s leadership in his diary, I suspect he takes more issue with Arthur’s visible attitude and less with the content of his complaints. (Specifically, Skelton felt Armitage could have been more careful and lowered the sledges first during a particularly tricky portion of the descent. As he did not do this, several of the men slipped, including Arthur, who cut his finger and nearly got his head bashed by a sledge.) These tense few days in January 1903 in Skelton’s diary are the only mentions I can find of Arthur’s involvement in any arguments, and this towards the end of a grueling months-long sledging journey. Overall, he seems to have been even-tempered, a strong asset on an Antarctic expedition.

The second winter descended on the ship, and it was quieter than the last. The men, Arthur included, knew the routine, and if the Antarctic winter had lost some of its excitement, so too had it lost much of its danger. Many of the same pursuits filled the second winter as the first, including the South Polar Times—now edited by Bernacchi, as Shackleton had been sent home with scurvy on the relief ship. Arthur continued to write his poems. His “South Pole Volunteers” in the April 1903 issue clearly channels a strong feeling among the sledgers that they were breaking their backs in pursuit of science for a distant world that knew not of their struggle. For all that the drudgery of the work is clear, Arthur also notes “But every camp has marked a spot / That men have called a home.” “South Pole Volunteers” has a pleasing rhythm that my poetry friend Branwell describes as Service-esque:

Ours are the shuddering nights on snow,

Arthur Quartley, excerpt from “South Pole Volunteers”, April 1903 South Polar Times

The march of lifelong days,

The pain and strain of aching eyes

Across a drifted haze.

Lonely at night in our tent do we lie,

While the cold blast o’er it blows.

The work we do, the death we die,

Not e’en a shipmate knows.

By beaten roads the old world goes,

With noise of work and pleasure.

But those who must, mid snow and gust,

Take out a new world’s measure.

We know just why the order comes,

“The Old World Wants To Know”

So we bend our backs til the harness cracks

And go onward o’er the snow.

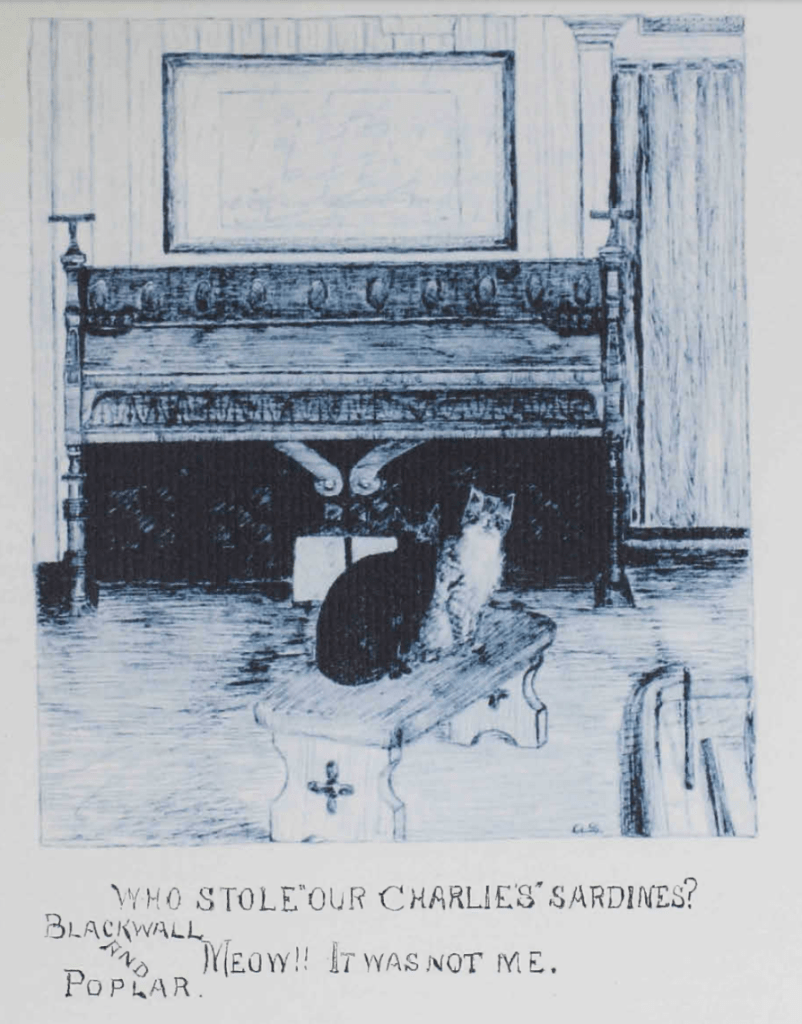

Physicist Louis Bernacchi ended up quoting part of this poem in his book Saga of the Discovery. In the same issue, Arthur also provided an illustration of the ship’s cats, Poplar and his own Blackwall, playfully denying being sardine thieves. There were only three issues of the SPT this second winter, but Arthur contributed to all of them with poems and illustrations. In the June issue, he wrote a poem called “To the S.Y. Morning” about the farewell to the relief ship, and drew Michael Barne and the “Flying Scud”, a sort of cart with a sail attached. In the August issue, which debuted as the sun was returning, Arthur wrote a poem appropriately titled “Sun-shine” in which the Antarctic animals return after winter.

For the summer 1903-1904 sledging season, Arthur was with Barne’s team. They were tasked with heading southwest to a latitude of 80 degrees. During Captain Scott’s farthest south journey the previous year, he and his team had seen tantalising land to the west, but, focused on attaining a high southerly latitude, had been unable to visit it to procude geological samples. Arthur and the rest of Barne’s team rectified this, collecting samples of granite that went a long way towards proving the continental nature of the Antarctic land. This journey in particular is oft-forgotten, though it contributed greatly to the expedition’s scientific results.

However, like all sledging parties, they had to be back at the ship early that season to aid with the efforts to free Discovery from the ice. With every other available man, Arthur worked at the sawing camp for weeks, futilely trying to cut a passage through miles of two-metre-thick ice to the ship until Captain Scott returned and ordered everyone to stop wasting their efforts. For a while it looked as if the expedition would remain another winter, but then the relief ships arrived with orders from the Admiralty to abandon Discovery if she could not be freed. Arthur was going home this season, no matter what.

This was a rough time for him for other reasons quite aside from the possible loss of the ship: Blackwall was sadly killed by the dogs. From Wilson’s diary: “The little black she-cat that has been with us the whole two years was found dead today, killed by the dogs. The cat belonged to Quartley, one of the stokers, an American, and he was devoted to it” (2 February 1904). There are some indications stoker Thomas Whitfield may have set the dogs on her, possibly due to some beef with Quartley. (It’s equally likely this may have had more to do with Whitfield’s own mental health struggles, which came to a head on the return voyage.) Blackwall had almost made it to the end of the expedition, too: by mid-February, the Discovery was freed from its icy prison by a combination of a swell and blasting efforts. Arthur and his crewmates made their way first to New Zealand (where Arthur was on the sick list for a while due an injured hand), and back to England in September 1904, where they received a hearty welcome indeed.

Thus ends the story of Arthur Quartley’s time on the Discovery expedition. Unlike many of his messmates, Arthur would never return to Antarctica. He did not go on, like Edgar Evans or William Lashly or Frank Wild or Tom Crean, to become a famous name. Instead, his later life was quiet, and I can find few details.

He never forgot Discovery. In 1906, while serving on HMS Petrel, he submitted an entry to a competition run by the Daily Mirror to find the “Queerest Christmas Present”. He was one of the second-prize winners for his piece “Only Little Lady in Antarctica”. He begins by explaining that Christmas was celebrated during Antarctic mid-winter (June) because during December everyone was split up in sledging parties. He then goes on to describe his gift:

Rummaging the hold of the Discovery we found among the many cases that were stowed there one that contained Christmas presents, thoughtfully placed on board by Sir Clements Markham, I believe.

Arthur Quartley, “Only Little Lady in Antarctica”, 26 December 1906 Daily Mirror

In the case were many things dear to the heart of the small boy, such as whistles, trumpets, drums, and mouth organs; but I think my present was the envy of the ship’s company, for it was a little girl-doll, and the only little lady that we saw for two years.

Arthur Quartley was promoted to Chief Stoker for his service on the Discovery. He continued to serve in the Royal Navy through the First World War, adding a Victory Medal, 1914 Star, and Meritorious Service Medal to his Polar Medal. He also found love during the war, getting married in early 1916 to Mabel Curtis Their first child, Arthur Lester St John Quartley, was born in July. After the war, he retired from service and became a clerk at a wholesale chemists’. He and Mabel welcomed another son, Donald Stephen Quartley (possibly named in honour of his little brother Don), in 1924. Arthur lived in England until the end of his life, and must at some point have become a citizen if he wasn’t already, because he appears in electoral registers. His sisters, Adele and Grace, travelled across the Atlantic many times over the decades, presumably to visit him. On 29 March 1945, he died in New End Hospital in Hampstead. He was buried on 4 April in Camden. Mabel survived him.

If you’ve made it to the end of this post, I hope you’ll agree Arthur Quartley had a fascinating life. There remain many mysteries: when and how did he learn to draw? From his father? Why did he join the Royal Navy? What inspired him to volunteer for Antarctica? For all the sources I can read, there are some things I will never know. I do think his story highlights the importance of documents like the South Polar Times. Without the newspaper, Quartley would be remembered only as a very strong sledger. One who was present for incredible discoveries like the first Emperor penguin rookery, yes, but there would be no recorded knowledge of his art. Quartley was a strong sledger, a fixture of the mess deck. He was also a poet and an artist with a unique view of the world, and an honest and distinctive style of expression. At no other time in his life does this come through. His sister Adele showcased a painting at a National Academy show; Arthur did not. It is only the SPT that preserves the memory of the artist he was, the man who took to the seas his father painted.

I took my ski

And my long ski pole,

The moon made the snow shine white.

I went my way to the top of the knoll,

It was the dead of night.I took the turn

Round through the Gap,

That runs by Crater Hill.

You can see this place, ‘tis on our map,

Then my heart froze, and stood still.For down Ski Slope

There shot a Soul,

As though from a crossbow.

He sat astride a long ski pole,

His ski touched not the snow.He held on high,

As he flew by,

A hand with finger bent.

His eyes looked cold as stars in the sky,

And round through the Gap he went.Then I shivered and shook,

And could hardly look,

For thinking of his end.

I knew that they who went that way,

Would surely perish in Pram Point Bay.I quickly thought to aid him,

And did not quite see how.

Then with all speed, I made my way,

To the top of Ski Slope Brow.

The run down through the Gap the only way left now.Then as I turned to take the run,

A shiver shook my frame.

There stood the man?

I’ll call him one,

His eyes seemed all aflame.He pressed up closely to my side.

His eyes they burned me through.

Then said to me,

(His soft voice lied),

A race, I challenge you.And if perchance you do beat me,

This then will I do.

I’ll give to thee,

My golden ski,

There will be no loss to you.We raced away,

Down long Ski Slope,

I had the best at start.

And now I’d led him all the way,

So hope was in my heart.By a foot I won.

With a mocking laugh

He gave me his golden ski.

Now he said, we race for my staff,

What are your stakes to be?Stakes cried I, you can’t beat me

You have lost your golden ski.

And no one, I stake my soul,

Could beat me with only a pole.

Done! said he.You will do well,

In the regions below.

What is that you say to me?

You ski well

You are not slow said he.At the top of the Slope,

His eyes burned blue.

Go! said he, away we flew

As across his staff,

A leg he threw.Then down Ski Slope,

We shot for the goal,

As though from a crossbow.

He sat astride his golden ski Pole

His feet touched not the snow.I was on the golden ski,

And soon I quickly knew,

Where e’er he went on his ski pole,

My ski went there too.

On, on toward the Gap we flew.He held on high,

As he flew by,

A hand with finger bent.

His eyes looked cold as the stars in the sky,

And round through the Gap we went.By Crater Hill we sped,

Observation Hill we flew.

Going where e’er he led,

Trying to beat him through,

For my soul was at stake I knew.Then with a mighty leap,

Pram Point bay below,

To perish in the deep,

With one long shriek I go.

And no one on earth shall know.Then I felt a terrible grip.

Hi! you’re waking up the men.

Some one shook me like a rat.

And a growl went round the ship,

As up in bed I sat.Oh! d-d-don’t shake m-me

“The Spook of Ski Slope”, poem by Arthur Quartley (“Sea Leopard”), The South Polar Times vol. I, August 1902

I am in terrible pain.

Today I fell while out on my ski

Ski Slope is an awful place to be,

And I’ll never go there again.

Sources:

Books:

–History of the first battalion naval militia, New York, 1891-1911 by Telfair Marriott Minton

–The Voyage of the Discovery by Robert Falcon Scott

–The South Polar Times, Volume I (ed. Ernest Shackleton)

–The South Polar Times, Volume II (ed. Louis Bernacchi)

–The Antarctic Journals of Reginald Skelton: Another Little Job for the Tinker by Reginald Skelton (ed. Judy Skelton)

–Two Years in the Antarctic by Albert Armitage

–Saga of the Discovery by Louis Bernacchi

–Diary of the ‘Discovery’ Expedition by Edward Wilson (ed. Ann Savours)

–Pilgrims on the Ice by T.H. Baughman

–Captain Scott’s Invaluable Assistant Edgar Evans by Isobel Williams

–Antarctica Unveiled by David Yelverton

Newspaper articles:

-“Personal”, The Daily Constitution (Middleton, Connecticut), 22 April 1875

-“Mortuary Notice”, New York Herald, 19 April 1875

-“Arthur Quartley”, New York Times, 21 May 1886

-“Personal”, New York Tribune, 11 July 1884

-“Mortuary Notice”, New York Herald, 20 May 1886

-“Pictures by Quartley and Smith”, New York Times, 25 April 1884

-“Local Matters”, Baltimore Sun, 8 April 1886

-“Arthur Quartley, New York”, Baltimore Sun, 20 May 1886

-“Local Matters”, Baltimore Sun, 20 May 1886

-“Mortuary Notice”, New York Herald, 23 May 1886

-“Fine Play at Tennis. Continuing the Tournament at Newport and Beginning at Staten Island”, New York Herald, 25 August 1886

-“Local Matters”, Baltimore Sun, 11 February 1881

-“Academy of Design. The Spring Exhibition at the Ventian Art Palace”, New York Herald, 3 April 1886

-“Rice and Old Shoes. A Large Supply Required for Yesterday’s Brides and Grooms”, New York Herald, 21 June 1888

-“Football Men at Play. Scoring Touchdowns and Goals on Many Fields”, New York Herald, 21 October 1888

-“Matrimony Notice”, New York Herald, 8 April 1890

-“Matrimony Notice”, New York Tribune, 8 April 1890

-“Sports on Staten Island”, New York Herald, 31 January 1892

-“New-York Won And Lost. The Team Again In Second Place”, New York Tribune, 21 August 1892

-“Rowing on the Kull”, New York Herald, 11 June 1893

-“Staten Island Boat Club Races”, New York Herald, 21 July 1895

-“Art Notes”, The Evening Post (New York), 5 December 1874

-“The Folks Who Sailed”, New York Herald, 29 May 1884

-“Matrimony Notice”, New York Tribune, 8 April 1890

-“My Queerest Christmas Present”, Daily Mirror, 26 December 1906 (accessed via British Newspaper Archive)

-“Naval Honours”, Hampshire Telegraph, 18 July 1919 (accessed via British Newspaper Archive)

-“In the Antarctic Night”, The Macon Telegraph, 14 July 1903

Records:

-US Federal Census, June 1880

-Arthur Quartley (1839-1886) naturalisation record

-Bedfordshire, England, Electoral Registers 1832-1986

-England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007

-England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005

-England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills & Administrations) 1858-1966

-Royal Navy Register’s of Seamen’s Services, 1848-1939

-Index record for Royal Navy medals

-UK Census, 1901

-Arthur Quartley Naval Service Record

Other:

https://barder.com/family/history/quartlys/ ((A personal blog post, but my Quartleys do seem connected to this Quartly family of engravers through Frederick William and Arthur Sr.)

https://www.woodvorwerk.com/index.htm (Excellent compilation of biographical info about the Quartleys; everything I found here was cross-checked)

Leave a comment