Midway down Ireland’s Dingle Peninsula, nestled in a beautiful valley between verdant hills, lies the small village of Annascaul. Most tourists come for the hiking: Annascaul is surrounded by excellent walking paths, and situated right along the scenic Dingle Way. When my girlfriend and I visited last August, we found Main Street (almost the only street) filled with seasonal B&Bs open to cater to these hikers—so much so that when we booked our room we were asked whether we would be arriving by car or on foot via the Dingle Way!

Well, dear reader, if you’re on my blog…you know I wasn’t there for the hiking.

Annascaul is the hometown of Tom Crean (1877-1938). A veteran of three polar expeditions, Crean played a crucial role in many of the Heroic Age’s most dramatic moments. He trekked 35 miles solo across the Great Ice Barrier, with nothing but some biscuits and chocolate in his pocket, in order to fetch life-saving help for the Terra Nova expedition’s second-in-command, who was dying of scurvy. He was one of the six crew members of the James Caird, fighting 800 miles across the frigid and tempest-tossed Southern Ocean to South Georgia to rescue the rest of the Endurance expedition—and when he got to South Georgia, he defied death again, climbing over mountains and glaciers to finish the job.

I’ve often called Tom Crean “the great equaliser” among polar afficionados. Whether you prefer Endurance or Terra Nova (or are a weirdo Discovery fan such as myself!), we all love Tom Crean.

My girlfriend and I visited Ireland last August. When we were planning our holiday, she asked “Is there anything polar-related you want to see while we’re there?”. Knowing the Shackleton Museum in Athy was closed for renovation, I offered “Actually, one of the guys from Discovery opened this pub in Kerry…” I wanted to see the town Tom Crean grew up in, where he lived and worked on his family farm until he joined the Navy aged 16—unbeknownst to him, on his way into history.

We arrived in Annascaul on an overcast but warm summer afternoon, having driven our rental car south from Burren National Park and crossed the Shannon estuary on the ferry. It was our last day in Ireland—the next morning, we’d have to wake up and drive all the way back to the airport. Our B&B was almost at the end of the Main Street—though not yet in sight of the South Pole Inn, our destination, which was on a roomy plot at the very end. As we checked in, the hostess suggested the South Pole Inn as a dinner option, causing us to just grin at each other knowingly.

Before food, however, we stopped at the Tom Crean Memorial Garden, across the street from the Inn. Here we found a statue of the man himself, holding ski poles and sled dog pups, the latter no doubt a reference to the famous photo.

There was also a stone from Grytviken, the old whaling station on South Georgia where Tom reached civilisation after the James Caird journey, and where Shackleton is buried. To complete the exchange, a stone from Minard, near Annascaul, was also taken to South Georgia.

Next, we approached the pub itself. The South Pole Inn was opened in 1927 by Tom and Eileen Crean. Retiring from the Navy and opening a pub had always been a dream of Tom’s old sledgemate, Edgar Evans, who died as a member of Scott’s polar party. I know I’m not alone in thinking of the South Pole Inn as at least partially honouring Evans’ dream, which no doubt the two discussed on many a long day of marching.

The building is brightly painted with orange accents. A sign with a penguin greets visitors, promising hot food, cold beer, and a warm welcome! The three windows in the front are decorated for each of Tom’s three expeditions: Discovery (1901-1904), Terra Nova (1910-1913), and Endurance (1914-1916). There’s outdoor seating, and a beautiful babbling brook running by.

Stepping inside was a rush of stimuli—laughter, warm air, sticky tables, the smell of food. Every inch of the wood-panelled walls was covered with pictures and newspaper articles about Tom Crean and his expeditions. We chose a high circular table with a good view of the goings-on, though it was early yet for dinner and there weren’t very many people about. I ordered a veggie burger and the Expedition Irish Red Ale, chatting with the waitress about the pub. She informed us that the South Pole Inn was no longer owned by the Crean family, but that the beers on tap came from a brewery that was.

While waiting for our food, I got up to explore the pub. More people were starting to arrive. I wandered through, relishing being in a place where polar chatter filled the air. I kept overhearing snippets of conversations like an emphatically searching “Why did they bring ponies??” and a sombre “He died in 1938.” I investigated the wall decor more closely, finding a picture of a white-haired, older Tom Crean, and a newspaper cutout about a young boy who did his school project on Tom. I flipped through the polar books stacked atop the mantle. In a side room, I admired the recently-finished scale replica of the James Caird. There was a cutout to drive home just how cramped it was inside, which had the added benefit of showing off the construction and pleasing my inner shipwright nerd.

Our food came, and was delicious. The whole time we were eating, folks kept coming up to a small wooden door in the wall just next to our table. Above it was a rhyme: “they say the eyes are the window to the soul…but here we have a window to the Pole”. Whenever someone pulled open the metal handle, a roar of icy wind howled out, and artificial snow spun round and round behind a glass. It was loud and wonderful! People jumped, and giggled, and the kids loved it. Parents kept apologising to us as their kid wanted to open it over and over—as if we weren’t enjoying it as much as their kids were! We lingered over our meal, soaking up the atmosphere. I tried to imagine the pub back in the 30s, when Tom Crean himself would have been sitting by the fire. I felt incredibly lucky to be there.

After we paid, we briefly parted ways as I decided to visit Tom Crean’s grave. The waitress had said it was about a mile away. The sun was setting, but it was doing so at its leisurely summer speed, so I calculated I had enough time to make it to Ballynacourty Cemetary and back before dark.

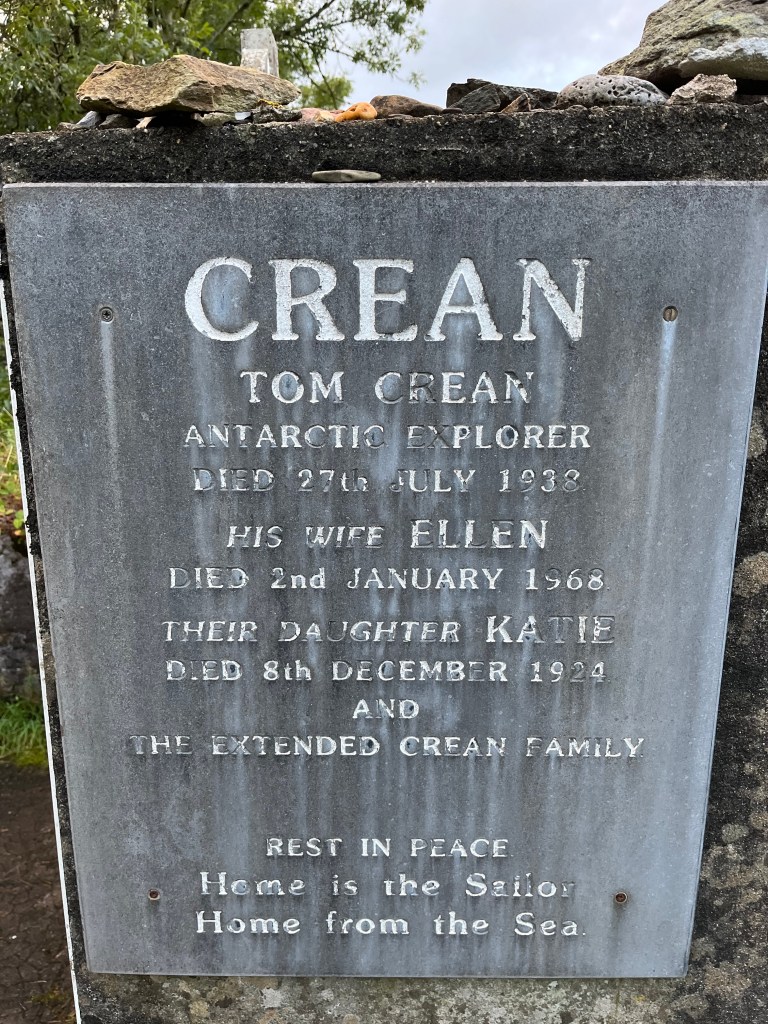

Tom Crean is buried with his wife and daughter Katie in the bottom corner of an old, moss-covered cemetary in the quiet countryside. As I paid my respects at his grave, the only thing I could hear was the roar of a stream behind me—I thought how appropriate that a sailor with “Home is the sailor/Home from the sea” from Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Requiem” as his epitaph should have running water nearby. Even though it is going on 90 years since Crean passed, his grave is decorated with a collection of flowers, shells, candles, and even a crochet penguin that people have left. It is clearly well-loved and cared for.

My visit to Annascaul was short but sweet. It gave me an opportunity to reflect on the extraordinary life of Tom Crean, as well as on the different ways people remember the lives of the men versus the officers of these expeditions. As I touched on in my recent post about Arthur Quartley, there are more written records about the officers, and thus they are easier to get a sense of the personalities of. The men—the sailors and stokers who did much of the work and without whom the expeditions never would have happened—often come off as a bit of a monolith in polar history books. Names without much information on character. It’s sad, and emphasises that history is recorded events of the past—for in reality, those of whom little was recorded were just as vibrant and alive as the officers. Crean is one of the best-known of the men, and in recent decades has been rediscovered as an Irish hero, his story taught to children in schools. Still, even with Crean, I cannot simply go read his firsthand diary or book as I could Scott’s or Shackleton’s. The bits and pieces I know of what he was like mostly come from others. Tom was not afraid to show emotion; there were tears in his eyes as he bade a final farewell to the polar party. Tom sang; Shackleton remembered Tom singing a song on the Caird, one he could never make out, and said that though Tom was “devoid of tune” “in moments of inspiration he would attempt ‘The Wearing of the Green’”1. Tom was funny; when Shackleton asked Tom if he would come along on the Quest expedition, Tom said no, explaining “I have a long-haired pal now”, referring to his wife2. He begins to come alive as a humble hard worker with nerves of steel, a song in his heart, and an effortless sense of humour.

When compared to the officers, very few of the men have physical memorials: statues, plaques, academic institutions, pubs, museums, or otherwise. Tom Crean is the exception. I am glad to have raised a pint to him in the South Pole Inn.

Leave a comment