(Disclaimer: This post is hugely self-indulgent and introspective. I’m hoping I’ve written enough Serious Research Posts that my readers will bear with me. I also sincerely hope aspects of my experience ring true for some of you.)

“Why are you so interested in polar history?”

It all started on June 6, 2022, when I visited a museum in Dundee. It was a crisp Scottish summer day, and my friend and I were looking for something to do on her second-to-last full day in the country. We hopped on the bus to Dundee and—

No, back up.

It all started in high school English class, when I got really attached to a poem we were assigned called The Cremation of Sam McGee. “There are strange things done in the midnight sun / By the men who moil for gold; / The Arctic trails have their secret tales / That would make your blood run cold; / The Northern Lights have seen queer sights, / But the queerest they ever did see—”

No, further.

It all started when I was seven years old, and read a story in National Geographic about Ötzi the Iceman. He lived 5,000 years ago, and now he was a mummy, his tissues, bones and organs preserved in ice. As much as his injured left shoulder and the undigested wheat found in his belly gripped me—how did he die?—it was the picture of him that really haunted me. The taut skin stretched over his skull. The flesh that should have decayed long ago. I was scared to go to the toilet at night, certain I’d see his face looming at me out of the darkness at the end of the hallway outside my bedroom. He inspired imagination and terror in me equally—

No, fast forward a few years.

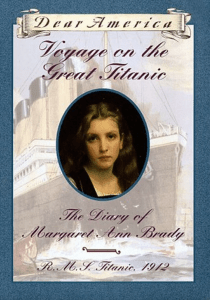

It all started when I was ten years old, and obsessed with the Titanic disaster. Picture a little girl who could name all the officers in order of rank from memory, who could tell you grim-faced about the ordeal of those survivors on Collapsible Lifeboat B, who balanced for hours through the night in the sloshing water atop an upside-down boat—that was me.

Yeah, let’s stick with this one.

Whenever my grandparents took me to the indoor waterpark near their house in Belgium, I ventured into the cold plunge pool. It was tiny, with room for only one person and just meant for a quick dip. With every slow step down, the mint-green water rose excruciatingly higher on my legs. Wincing, I thought of Titanic’s Second Officer Lightoller’s quote about the North Atlantic that April night being like “a thousand knives being driven into one’s body”, and forced myself to go deeper. On account of not speaking Flemish, I genuinely have no idea what the other pool patrons thought of this skinny little kid fully immersing herself in the frigid water. But it must have proved an odd sight, especially backdropped by all the other kids screaming down the waterslide. Holding my breath, I ducked my head under and curled into a ball, dead to the outside world, feeling my heart thud and my skin start to numb in the silence. I floated there for about ten seconds—all I could take. In some painfully naïve way, with all the earnestness of a nerdy child who reads a lot about hardship but is privileged enough not to have experienced it herself, this was my attempt to honour them. The Titanic victims.

(Of course, the water in the cold plunge pool at LAGO Pelt Dommelslag was not as cold as that which the Titanic passengers experienced. I can’t remember the exact temperature, nor can I find it on the pool’s website today. From images online it looks like the area I remember the cold plunge pool being in has been filled in and is now home to a planter. But I can say it was take-your-breath-away cold. Unhealthy-to-stay-in-longer-than-a-minute cold. Ten-year-olds-probably-weren’t-allowed-in-and-that-sign-couldn’t-stop-me-because-I-couldn’t-read-Dutch cold. Maybe that’s why they removed it…But even if the number is gone from my memory, I remember they had a temperature label and I read it and concluded at the time that it was a few degrees warmer than the Titanic water. It was close enough. And that’s something I trust Little Me to have been rigorous about—I was nothing if not a serious kid.)

At some point over the ensuing years, my lifeboat rowed away from Titanic. But an old obsession leaves a mark. Well-trodden neural pathways about Edwardians, hubris, frigid cold, noble sacrifices, poignant art amidst tragedy (e.g. the orchestra playing to the end)—all the groundwork was laid for me to fall in star-crossed obsession with one Robert Falcon Scott. Reader, it was not a question of if, but when. The real question is how I managed to avoid him as long as I did. Historically, the sinking of the Titanic and the death of Robert Falcon Scott took place within a few weeks of one another, but the world didn’t find out about the latter until a year after it happened. It took me 16 years after my Titanic obsession to find Scott in his tent. But I got there eventually. There are certain ingredients in narratives—be they real or fiction—that draw me in again and again.

It was Scott’s birthday, the first day I went to Discovery. June 6. If you’re the sort to look for signs, there’s one. Not that I even knew who Scott was when I walked through the doors…

It can be hard, in the aftermath of knowledge, to reconstruct what one knew before an obsession. If I could interview the me of three years ago, I’d love to ask her what she knows about polar history. Certainly she’d heard the name Shackleton before, and knew he had something to do with the Antarctic. She knew Amundsen was the first at the South Pole. She’d also come across the bare bones of Oates’ end1—the immortal phrase “I am just going outside, and may be some time”—and had a quiet cry to herself about what dire circumstances must have forced someone to make such a brave and terrible decision as to walk out of that tent. That, to the best of my straining brain, is the sum total of past me’s polar knowledge.

That first time at Discovery, I didn’t stay long. We had a dinner reservation to keep, and my friend was not a fan of the mannequins that used to pepper the ship (there’s fewer now; they’re slowly being removed). It was a lazy Monday afternoon and we didn’t come across another living soul the entire time we were belowdecks, which only added to the eerie effect of the mannequins. Every room we entered, I poked my head in first and “cleared it”, issuing a warning like “one at ten o’clock” to prepare my friend. But even as we whirled our way through, not knowing bow from stern, various factoids caught my eye. Scott and his men put on plays and published a newspaper through the winter months of complete darkness. There were cats. A sailor died falling from the crow’s nest. A scientist brought two penguin chicks aboard and they lived in his cabin. I filed these away, knowing my ticket was good for a year. I’d be back. I had a strong sense the ship had more to tell me.

Also, I gathered that this Scott fellow died. In Antarctica. Not on Discovery, but ten years later, on another expedition. He slipped away into frozen oblivion, after writing to the bitter end.

This didn’t fully register emotionally during my first visit. It hit harder the second time, when I tried to decipher Scott’s laboured handwriting from an image of his final diary page, and learned his last words were a plea for his family to be taken care of. By my third visit, in August, I was fully hooked—though it still took me several months before I really started diving into the literature in December 2022. I fell into polar slowly, then all at once. If the ways the Discovery crew stayed sane over the polar winter were what initially drew me in—having recently spent 14 days stuck in a room by myself as I quarantined upon moving to the UK, I had had the pale shadow of a similar experience—it was Scott himself, and his story, that really anchored my interest as I started devouring books.

Life-changing can be an overused phrase, but it is apt here. My polar obsession has made me new friends; I’ve travelled to new countries, taken vacations in archives of all places, presented research talks to learned societies, and landed the greatest part-time job I’m likely ever to have. I’ve found myself alternately hiking to a grave at the far end of the Dingle Peninsula in Ireland, shovelling accumulated rust off the keel blocks underneath Discovery, holding a dead man’s sketchbook in the archives of the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, or being given an impromptu ecclesiastical tour of the Essex/Suffolk border by the nephew of Apsley Cherry-Garrard. Sometimes I truly have to pinch myself to make sure I haven’t fallen asleep and woken up in someone else’s life! Thus far I’ve painted a picture of a child drawn to stories of tragedy, survival, cold, science, wonder, and perhaps most importantly the unknown, a child predisposed to obsession—who one day as an adult came across a new subject that reawakened this youthful vigour, and whose life will never be the same.

So….why?

I don’t know that I can really answer that question. If that feels like a cop-out, I’m sorry. I will try. Simply explaining my predilection does not feel enough—that only alters the chronology. For me, Antarctica feels like a place I didn’t know I needed, but have been missing my whole life. Why?

Why would anyone want to go to such a cold, miserable, lethal place as Antarctica? It’s a question the explorers were often asked in life. Biographers still shout it at their ghosts in ink. Sometimes their families were asked it after they died. The explorers found it hard to explain, too. Scott cited science, Shackleton evoked the lure of little voices, Amundsen wanted to be first. But there were more practical reasons, too: Scott wanted to make a name for himself to support his family after he became their sole breadwinner; Shackleton knew a career in the merchant navy alone would not win him the approval of his would-be father-in-law; Amundsen…well, okay, Amundsen’s a bit of an outlier here. He always wanted to be a polar explorer, come hell or high water. But all these men had to come up with reasons in order to defend their enterprises to their creditors, pitch their ideas to potential donors. Yet when all their showmanship is stripped away, it can be hard to not feel the real answer is simply “because I want to”. One thinks of Mallory’s “Because it’s there.”

Is it fair to compare the reasons for my armchair interest to the explorers’ “why” answers? Well, Lord knows I want to get out of the armchair and go to Antarctica. Badly. I joke that some people have get-rich-quick schemes, but I have get-to-Antarctica schemes (some of which are more like get-poor-quick schemes). Someday, one of them will work. Like many before me, I have fallen for the pole. This might sound a romantic, even woo-woo, notion, but it is very real. The magnetic draw of the poles does not exist only in the scientific sense2—people fall in love with these places. Many of the explorers—Shackleton, Amundsen, and Frank Wild come to mind immediately—never quite felt comfortable when they weren’t out exploring. Even Scott, who I maintain could have had a happy, quiet retirement (very much not a given among polar explorers!), clearly feels stifled and choked within the confines of the Navy when he returns from the Discovery expedition—all he wants to do is plan his next venture. They got antsy, restless, couldn’t sit still at home—and I, too, feel the urge to go South. My blog header about polar madness is not entirely tongue-in-cheek. I want to go to this strangest of places on Earth, where days and nights have different meaning, where humans did not tread until very recently3, where one feels one is on an alien planet. Peculiarly, I expect I’ll find some comfort in that vastness.

Yearning for empty horizons brings to mind a particular sticky point for me in my self-examination of my Antarctic interest. I discuss it in my post on Antarctica and space: that there is an evocation of manifest destiny and colonisation through exploring, imposing the human will over a landscape. Polar history is a topic that has been tightly tied to ideas of imperial glory, and the otherwise-outdated Great-Man school of history4. I’ve heard historian friends discuss how it and maritime history are often-insular fields that can be behind the times and slow to open up to areas like sociology and global studies. I have seen a worrying tendency among some other polar history types to claim early Antarctic exploration as a sort of unproblematic, “pure” exploration free of any of that troubling exploitation of native peoples so prevalent in other histories—the implication being that here, at last, are some “guilt-free” heroes for them to admire. Others don’t even try to hide their imperial glorification. I’ve had a visitor on Discovery, an old man, come up to me with tears in his eyes and say that he was happy to see the great polar heroes still being celebrated somewhere in this “anti-imperial age”. In the moment I was hog-tied by my positionality as an employee and correspondent need to be polite to customers, and simply changed the subject while giving no hint of agreement with his statement. But here in the freedom of my blog I can be uncompromising in saying that I do not stand for any glorification of the colonising agenda of the British empire. Make no mistake: these explorers had colonising agendas, and they brought their prejudices with them to the ice. I’ve touched on this already in my post on Arthur Quartley, which discusses the minstrel show during the Discovery expedition, and will probably have a more in-depth post on Antarctica and empire someday. The more academic side of polar history is currently producing excellent scholarship engaging with empire and colonialism, but these subjects are lacking in the popular histories—this is something I hope will change, and I hope to be part of that change.

I am not interested in the uncritical hero-worship brand of being a polar historian. I’m not even sure I’d call those types historians, beyond the listing of bare-bones facts of dates and figures; I should note this approach is most prevalent among the plethora of popular polar histories that exist. This is not me being elitist; there are some excellent popular histories out there, but one really must put in the research and present subjects ethically and fairly. History implies analysis, contextualisation, acknowledgement of a historiography and construction of an argument. Blind admiration and hagiography does none of this. Also—and much less seriously—I find a subject without flaws b-o-r-i-n-g.

As the great Florence (of “The Machine” fame) sings in “No Choir”:

And it’s hard to write about being happy

‘Cause the older I get

I find that happiness is an extremely uneventful subject

Another cycle still in vogue in polar that has gone out of style in other fields of history is the rehabilitating-debunking cycle that various polar figures go through. I’m a bit tired of it. I think that both the cancel-culture-style ignoring of these figures because they were imperialists, and the “your fave was an amoral idiot, actually” debunking biographies5, are not especially helpful ways to examine (or not examine) polar explorers. It should be possible to admire these men for their talents, their humanity amidst hardship, and, yes, their heroic feats, while considering the totality of their flaws and beliefs and positionality within empire, how their reputations and stories have been used for various agendas over time, and indeed how we are using them in the present. The past is a foreign country, as they say—but thinking we are always, all-the-time better than those who came before us is counterproductive and can actually blind us to our own shortcomings—surely in a hundred years there will be plenty of things we are unthinkingly doing right now for which future people would cancel us or think “how could they have done that? Didn’t they realise?”6. I think it is less valuable to consider what we would be like if we lived back then or what they would be like if they lived today—a futile exercise—and more valuable to look at the past and see where it echoes, touches, influences today. We should study the past, because it shines a light on the present. We should not glorify it. We should not ignore it or belittle it. It contextualises our world.

Now that I’ve planted my flag…

…why am I interested in polar history?

Given the above—and my own experiences feeling very young and very female in rooms of polar history buffs7—it’d be easy to say I’m outside my demographic here. Or am I? Historian Francis Spufford, in his excellent cultural history of polar exploration, notices an interesting trend of women—and I’ll add that many of them are left-wing hippie types like myself, even better—becoming deeply invested in polar exploration specificially:

Here began a continuing tradition by which women otherwise sceptical of heroic masculine agendas granted exploration an exceptional sympathy, seeing, in their thwarted attempts to ‘conquer’ the ice, men learning what women knew. Men fighting other men in wars might wrestle sympathetically with loneliness and fear, but men confronting an implacable environment which was, by definition, stronger than them, might grow to experience the female variety of grace under pressure, for which ‘resignation’ was an inaccurate word, though a reliable pointer. It did not mean surrender; it was more a species of self-preservation in the face of circumstances that could not be changed, a deliberate decision to inhabit the impossible situation on one’s own terms, rather than flailing uselessly against it. Explorers seemed to have grasped it who, for example, chose to care for each other in extremis rather than seizing the last minimal chance for survival. The importance of co-operative virtues in exploring was significant: like women in households, feeling the tug of demands from many directions at once, the explorers appeared to have to manage their crises in company, paying as much attention to the psychological needs of their companions as to the outward tasks of cooking and sledging.

Francis Spufford, I May Be Some Time: Ice And The English Imagination (1996)

When I first read this paragraph, my breath hitched. I took a picture of the page, highlighted it, and texted to half a dozen friends this is it!! This is why I care about polar history!!! The on-ice inversion of gender roles, the theme of the sublime…Spufford captures something familiar here, the sort of domesticity and humanity at the heart of all my old childhood disaster and survival stories.

And I’m not alone. I’m interested not only in polar history itself, but in others who, like me, have fallen head-over-heels obsessed over it. Bea Uusma wrote The Expedition about her attempt to piece together the mysterious fate of Andrée’s lost balloon expedition to the North Pole in 1897, weaving together the narrative of her dive into obsession in the present and the men’s crash landing on the ice in the past. Ursula Le Guin, the famed science fiction author, was an avid reader of polar history and explored its social aspects; her The Left Hand of Darkness, while fictional and set on an alien planet, features at its core a sledging journey that the “Heroic Age” figures would surely be proud of. Sue Limb wrote her biography of Captain Oates after, as a schoolgirl in the 1960s, she sent a Christmas card—essentially, fan-mail—to Oates’ old colleague Frank Debenham and he introduced her to Oates’ sister. More recently, former Disney animator Sarah Airriess gave up her animation job and moved to the United Kingdom to embark on a multi-year project to adapt Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s expedition account The Worst Journey in the World into a series of graphic novels. Allegra Rosenberg started Terror Camp, an online fan/academic conference for polar history buffs inspired by the TV show The Terror. Clearly there is a thread here of women who might otherwise be turned off by Boys-Own-Adventure style hero stories being utterly fascinated by polar exploration, both before and after Spufford wrote in the 90s. Several of the people I’ve listed in this paragraph are now friends of mine—I have found a welcoming community here.

Does that help? I worry this piece is turning into a muddle, but I think there’s some gold amidst the mud(dle) to explain my why. Everything here thus far is probably as close as I can get to answering “why polar history?”, so that leaves….”why Scott?”

Scott is my favourite of the polar explorers. This is not a very popular thing to say these days, when Shackleton tends to be the crowd-pleaser8. A best-selling 1979 book by Roland Huntford, Scott and Amundsen, painted a negative image of Scott as a “bungler” that has remained in the public consciousness ever since—this is one of those reactionary debunking biographies discussed above9. Perhaps I’m drawn to Scott simply because I am a writer and scientist, and those are what he should have been. But when I read his diary in Scott’s Last Expedition, or his earlier expedition account Voyage of the Discovery, I can’t help but be charmed by him. He is complex: endlessly self-effacing, anxious, temperamental, yet with a keen interest in science, a love of his crew, and a persistent drive and ambition to achieve his goals. He is also a writer at heart—I firmly believe he was in the wrong profession as a Navy man, and would have been happier as a science manager or author—he describes the beautiful natural environment of Antarctica in a way I have seen no other “Heroic Age” explorer emulate. Compared to others who write of nature as an antagonist that can be beat back with technology and grit, he seems to realise nature is stronger than him.

Here, for example—I’ll share a quote from Voyage of the Discovery.

In the midst of these vast ice-solitudes and under the frowning desolation of the hills, the ship, the huts, the busy figures passing to and fro, and the various other evidences of human activity are extraordinarily impressive. How strange it all seems! For countless ages the great sombre mountains about us have loomed through the gloomy polar night with never an eye to mark their grandeur, and for countless ages the windswept snow has drifted over these great deserts with never a footprint to break its white surface; for one brief moment the eternal solitude is broken by a hive of human insects; for one brief moment they settle, eat, sleep, trample, and gaze, then they must be gone, and all must be surrendered again to the desolation of the ages.

Robert Falcon Scott, The Voyage of the Discovery (1905)

Does that not just make you shiver? It could be out of a work of cosmic horror. Indeed, Scott was strongly motivated by the unknown and even the unknowable. This inspired him to want to solve the mysteries of the ice, weather, magnetism—and as he put his critical mind to these problems, he became an excellent scientific leader, as noted by many of his colleagues10. Scott was mercurial, and in his sanguine moments this motivation manifested in science and wonder—in his depressive spells the unknown could feel insurmountable.

People often find Scott at the end of his life—the first words of his they read are his last, a powerful and haunting plea as he lay dying in a tent on the Great Ice Barrier in 1912, having come in second after Amundsen in reaching the South Pole—but I encourage more people to learn about his life. A revealing facet of Scott to me is his relationship with Kathleen, his wife. Had he not married her, history would remember a very different Scott—the stiff, proper Naval officer would loom large. But if a stiff, proper Naval officer were all he was, would he marry a vagabond sculptress who slept under the stars? Scott and Kathleen at first glance seem opposites, but their choosing of each other reveals much about both. During a breathless courtship, they sent each other a flurry of anxious (mostly on Scott’s part) letters about whether or not they ought to marry. Scott’s love letters at times achieve sheer poetry:

How dare you tell me to stop loving you now? My precious girl—how dare you. Knock a few shackles off me and you’ll find as great a vagabond as you but perhaps that won’t do. I shall never fit in my round hole—The part of a machine has got to fit—yet how I hate it sometimes—oh by nature I think I must be a free lance. Among uncertainties this is certain. I love the open air, the trees, the fields and the seas—the open spaces of life and thought. Darling you seem the spirit of all these to me though we have loved each other in crowded places—I want you to be with me when the sun shines free of fog.

Robert Falcon Scott, letter to Kathleen Bruce, 28 May 1908, quoted from David Crane’s Scott of the Antarctic

Both these examples are much less read than Scott’s final diary. Part of the reason the diary is so remembered is that it achieves an unpolished candor and immediacy—because, of course, Scott never got to edit it. But The Voyage of the Discovery, which he did edit, is much better than people realise, a true classic of travel literature, and proves that Scott was an engaging writer when he was able to sit and revise as well as when he was at death’s door. His letters to Kathleen were the opposite in terms of intimacy—none but her were ever meant to set eyes on them. Here Scott’s worries and dreams were on full display, he wrote freely of his frustration with the way the Navy stamped out his individuality. Going to Antarctica opened his eyes to the possibilities of life outside the Navy, and marrying Kathleen was another step away from the Senior Service. By the time the Terra Nova set sail, he could hardly ever be seen in his Navy uniform in photographs, as if he was asserting his independence by being his civilian self. This and much more turmoil and yearning are to be found only in his love letters—my emotions reading them are best summed up by a line from the character Kathleen in Ted Tally’s play Terra Nova: “I was promised a smashing celebrity, and I got a haunted man”.

Polar history is only one of the times I’ve gotten into an obsession to find Ursula Le Guin has already paved the way. In her essay “Heroes”, she reflects on her interest in Antarctic expedition literature, explaining how it inspired both Left Hand and her short story “Sur”. In dissecting a diary quote of Shackleton’s, she writes of how silly it was of him to describe nature as an enemy when it was Shackleton himself who placed all the obstacles in his own path. Comparatively considering Scott’s final words, Le Guin analyses why she cannot, despite trying, find them “silly”:

But Scott, who did nearly everything wrong, why have I no such contempt for Scott? Why does he remain worthy in my mind of that awful beauty and freedom, my Antarctica? Evidently because he admitted his failure completely—living it through to its end, death. It is as if Scott realized that his life was a story he had to tell, and he had to get the ending right.

I am surely guilty of viewing life through a lens of story, of narrative. My reading interests have guided my academic ones, my career—my favourite genres have always been historical fiction and science fiction, and lo and behold, polar history and astronomy currently occupy all my time. This truth about myself forces me to confront my purpose: am I a fan? Am I an academic? I’m both, and depending on my current activity I can shift more fully into one or the other. It is a slippery slope, a strange tightrope to walk, and I try to stay well-aware of the dangers. I see this as my duty. If ever I fall off the edge, I’d rather know it, so you have permission to tell me.

But if I see everything as narrative, at least it means I am good at identifying narratives: their artificiality and their power. Scott’s is persistent because he managed to control it, to write himself a kind of victory from the jaws of mortal defeat. Le Guin goes on to say that his selfish traits as a writer allowed him to “win Antarctica” for us—for writers. I would add that Wilson and Scott were the first Artist and Writer, respectively, at the South Pole, and that it is for this reason—their unique ways of viewing the continent—and Scott’s especially, for me, as a fellow writer—that I am truly enamoured with them. Scott found himself, in Antarctica—through answering questions with science, pondering the mysteries of nature, and writing it all down.

I think the little girl who was mesmerized by Ötzi, who held herself under the numbing water for the Titanic victims, would understand—here, after all, is another frozen man…

I began this post writing about my first time at Discovery. You may well be surprised Discovery has featured so little in the story of my why11. That’s fair. The truth is, as much as I love her, as much as it feels blasphemy to say so—strictly speaking, it is not the ship herself that interests me. It is her history.

So, that’s as close to answering why as I can articulate here at the present. The only way I can get closer to answering why is to keep reading—but make no mistake, it is an asymptotic growth.

How about you? Why are you interested in Antarctica?

- I have a vague memory of seeing a tumblr post about this sometime during undergrad ↩︎

- Yes, I know the magnetic and geographic poles are different (astronomy degree here!), please forgive the metaphor ↩︎

- It seems no one spent long periods of time in Antarctica until the 1800s, but there is evidence Polynesians found it long before ↩︎

- I’m closer to the Annales school, studying the lives of ordinary people and long-term social change ↩︎

- Fascinatingly these types of biographies and re-examinations of historical figures as “bad, actually” can come from any part of the political spectrum, and often reveal more about their author than the historical figure ↩︎

- Our society’s collective abysmal treatment of disabled people comes to mind, as well as microplastics and carbon emissions, and surely there are many I cannot predict ↩︎

- I’m literally a #WomanInSTEM and polar really takes the cake on making me feel out of place demographically ↩︎

- You can rest assured that my love of Scott does not mean I bear any ill-will towards Shackleton. I wouldn’t have read 2.5 biographies of the guy and several books about Endurance, or given a talk about him at the RGS, if I did! ↩︎

- For a really insightful rebuttal (by a scholar of Sally Hemings) of a debunking biography of Thomas Jefferson that lays out the way these biographies end up telling on their authors rather than their subjects, check out this piece ↩︎

- Scott and science is a topic I want to write a paper on someday. His defenders often point to his affinity for science in their defense of him, but no one has quite detailed this affinity to my satisfaction. I want to dive into Scott’s education, his choice of more scientific pursuits in the Navy (torpedos), his contributions during his expeditions, and how his scientist colleagues discussed his scientific interests. ↩︎

- There’s been a lot of self-discovery, thought! (Okay, I’ll boo myself…) ↩︎

Leave a reply to Jim Cancel reply